We've all heard the stories: So-and-so, the now-famous author, had 537 rejections before her now-timeless classic was picked up by a little-known publisher and rapidly leaped to the top of the bestseller list through word-of-mouth alone. Her earlier book, which had previously sold 17 copies, all purchased by the author’s mother, was subsequently reissued and also became an overnight bestseller. Oprah chose it as her Book-of-the-Month club selection, and invited the author onto her show. She now lives in a castle on the Isle of Wight and has a seven-book deal with Random House, receiving advances that are larger than the Gross National Product of Finland and Luxembourg combined. She writes every morning and frolics with her pet alpacas in the afternoons.

I hate when that happens. It feels as if God has whimsically—perhaps even sadistically—rolled the dice and randomly selected one of thousands and thousands of deserving writers to win that ever-elusive and rare fame-and-fortune author’s lottery. (Although something Dan Aykroyd said comes to mind: “If you want to be rich and famous, try rich first, you might find that it’s sufficient.”)

It gets even harder when success visits a personal friend, for then I have no choice but to rise above my petty, childish envy, muster up some genuine-sounding enthusiasm, and pretend I’m tickled pink by his success, critical acclaim, and having his likeness plastered on the cover of the Sunday Times Book Review, hailed as “the Dostoevsky of our generation.” I know I speak for hordes of writers when I say, “What am I, the chopped liver of our generation?”

Writers generally have a deeper passion and far more serious purpose for pursuing their craft than the surface glitter of fame and fortune, which is highly unlikely to be the result in any case. At our best, we actually have something worth saying that someone else will find worth hearing. And that essential communication occurs regardless of sales numbers. Just one reader responding to our work with gratitude should really be enough for us. “Change one life,” they say in the Jewish tradition, “and you change the entire world.”

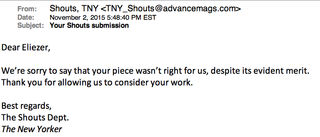

Nevertheless, I’ve noticed my jealousy arising even if it’s not the bestseller/Oprah scenario, but just a friend landing a modest deal with a small publisher. Or someone getting a one-page humor piece accepted by the New Yorker. Even a Letter to the Editor in the New Yorker bugs me, because those letters are to the very same editors that seem to take perverse pleasure in not only rejecting everything I’ve ever sent them, but to add insult to injury, in not even bothering to tell me that they were rejecting me. In fact, at this point, when I recently received an actual rejection note from the New Yorker for the first time in my life, I was thrilled! It felt like a major victory: I exist! And someone over there knows it!

But virtually any success for another writer, whether monumental or innocuous, brings with it an involuntary twinge of this syndrome—this smallness— despite the fact that ironically, these lesser successes and breakthroughs have also happened for me. Many times! But it’s somehow just never enough, as Jim Carrey so aptly put it at the Golden Globes this year:

.jpg?itok=kUkSWer6)

“Thank you, I am two-time Golden Globe winner Jim Carrey. You know, when I go to sleep at night, I’m not just a guy going to sleep. I’m two-time Golden Globe winner Jim Carrey going to get some well-needed shut-eye.

“And when I dream, I don’t just dream any old dream,” he continued. “No sir! I dream about being three-time Golden Globe winning actor Jim Carrey. Because then I would be enough. It would finally be true. And I could stop this terrible search for what I know ultimately won’t fulfill me.

“But these are important, these awards…I don’t want you to think that [the Golden Globes don’t matter] just because if you blew up our solar system, you wouldn’t be able to find us, or any of human history with the naked eye…[because] from our perspective, this [award] is huge.”

Just like, from our perspective as writers, getting published is huge—for about 23 minutes, in my experience. I have to restrain myself from telling writers who are on the verge of releasing their first published work, clearly believing it to be an event second only to the Big Bang in the history of mankind, that in fact, as I myself was once warned by an article, “Your book won’t change your life.” Could there be anything more sobering to hear than that, just when your life-long literary dream is about to come true at last? No, there isn’t; so I bite my tongue.

The concomitant of professional jealousy is schadenfreude. I admit it: when I fail to see a particular author’s book on the shelves of Barnes & Noble, I experience a moment of consolation, if not outright glee. Well if her books aren’t here, I think, then I shouldn’t feel bad that mine aren’t.

Thankfully, at least I’ve been lucky enough to be on the other end of professional jealousy at times. It’s as if there is a publishing ladder of some kind, and everyone is jealous of the person just one rung above them while being simultaneously gazed at with longing, envy and just a tinge of hatred by the person one rung below. It took me awhile to recognize this look in others, to realize that in their eyes, I was a published author, while they were still on the other side of that seemingly impossible abyss, still dreaming and hoping that one day they, too, would be welcomed into the club of “real” writers, published by real publishers. (Self-publishing and Kindle and all of that doesn’t count. Someone else has to publish you for it to mean that you’ve been accepted by the literary community, that elite group of your, yes, peers.) And you can never see over the shoulder of the person above you. The people below would never guess that I am jealous of the next person up the ladder, whose books are on the front table at Barnes & Noble, whereas to purchase mine you have to go ask the guy at the information kiosk to look through the online database of Books in Print and order them.

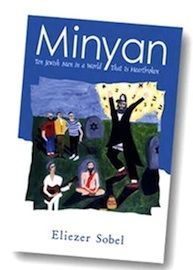

My novel, Minyan: Ten Jewish Men In A World That Is Heartbroken, was published in hardcover in 2004 by the University of Tennessee Press. It was selected by National Book Award winner John Casey from 400 other entries as the winner of The Peter Taylor Prize for the Novel, which is second only to the Pulitzer in its notoriety. Or possibly third, after the National Book Award. Okay, only a handful of people anywhere have ever even heard of Peter Taylor. I certainly hadn’t, but trust me, I’ve since learned that apparently there are lots of people who do know and love Taylor’s work, and the prize was a fairly big deal in those circles. Albeit, small circles. Dots.

I stumbled upon the entry requirements for the contest in Poets & Writers magazine. I was truly ecstatic when I learned I had won, and vocally yelped in my car. (I am a lot of things, but I am not typically a yelper.) I was especially excited because Poets & Writers frequently regales readers with stories of how being a contest winner opens all sorts of professional doors: invitations start rolling in to be on the faculty of writing conferences, or be a guest instructor at university creative writing programs; publishers reach out to them, offering sizable advances for their next book; numerous appearances and readings are scheduled, etc. etc.

The Peter Taylor Prize provided $1000 plus having the book published by the University of Tennessee Press, certainly respectable in literary circles. My writer’s ego was assuaged, temporarily—for more than 23 minutes, as it turned out, nearly two weeks!—but Minyan never earned any royalties, and though I waited patiently, none of those mythical doors swung open. The book, taking me with it, rapidly disappeared into obscurity among the 2,000,000 or more titles that are published each year in the United States, including traditionally published books, print-on-demand and self-published books, and all other possible formats.

To be fair, the publication of Minyan did open a small handful of doors. They weren’t even doors, really; more like transoms. Or little cat doors, maybe. I enjoyed four or five days of not-exactly-fame with a handful of readings in a few cities, including one for an audience of three elderly women in downtown Nashville. I sat on a few panels in my hometown, did one appearance at an afternoon Hadassah gathering at a JCC, was the guest on a radio show that aired at 3am in Kansas for a handful of farmers awake at that hour, and received a smattering of reviews in local free newspapers.

My incredibly generous father invested $14,000 for me to hire a fancy New York City publicist who, in exchange for that sum, produced exactly no results whatsoever. No talk shows, no reviews, no nuthin’. So although I did receive many gratifying letters from people that weren’t my friends or relatives, Minyan ultimately fulfilled precisely what that article had long ago warned: my book did not change my life.

Today, 12 years and 24,000,000 new titles later, you can find copies of Minyan in hardcover on Amazon for .01 cents plus shipping. ‘Nuf said. My lifelong dream of being a real writer with a real published novel had come true; and here I am.

The book, however, was priced at a hefty $32, which probably doomed it from the start. My own mother told me she was waiting for the paperback. And apart from the high price tag, it never really got a proper chance, in terms of promotion. Then it suddenly dawned on me a few months ago that I could give Minyan another shot, a second life in the digital world. (Duh. But I am 63. Old school.) So I’ve finally gotten around to making it available as a Kindle, Nook, iBook, and a paperback, (and this article is in fact a thinly-disguised attempt to get the word out.)

Nevertheless, it is ironic that it used to go the other way: if self-publishers were successful enough, which was rare, eventually a real publisher got wind of it and picked the book up “legitimately.” I did it backward: I had the real publisher first, and it did poorly enough that I picked it up!

And now maybe you’ll pick it up. My sense of personal worth, life purpose and masculine identity literally depend on it. With your help, I still have a shot at being enough. And please know that if I hit the digital viral lottery, I sincerely welcome your resentment, scorn and jealousy. You don’t have to pretend for me; I’ve been there; I really do know how you feel.

I would hate me too.