Spirituality

A Christian, a Hindu & a Muslim Walk Into A Bar…

And they're all Jewish!

Posted March 29, 2016

My spiritually formative years took place during the “me-decade”—the ‘70s—a time when self-help workshops were all the rage, and spiritual teachers and gurus from multiple religious traditions and cutting-edge New Age philosophies were attracting huge numbers of followers.

Although I dabbled in nearly all of them, none ever truly “took”; I seemed to lack the True Believer gene, and always remained a spiritual dilettante, getting tastes of what each path offered but never staying for the full meal. Swami Ramakrishna (circa late 1800s) famously said about spiritual practices, “If you dig a great many shallow holes, you will never reach water; instead, dig one deep hole.” I dug a ton of shallow holes, and as a result, I’m still dying of thirst.

There actually is one path, however, that has remained fairly consistent throughout my life: a great interest in the creative process, exploring it through writing, painting, dance, theater, playing and singing music, and I have lead many intensive workshops over the years on creativity as a spiritual path.

Thus one summer I was invited to a month-long ecumenical conference to represent the “Path of the Artist” alongside my fellow presenters: a Christian monk, a Buddhist dharma teacher, a Rabbi-in-training, and an Islamic Sheikh. Apart from the Christian monk, all of the other teachers were Jewish by birth.

The Jews are considered by some as having a disproportionate influence in both Hollywood and on Wall Street, but who knew that they were also a powerful force in other religions? There were so many emerging Jewish-Buddhist teachers and practitioners back then that the term “JuBu” came into being. Ram Dass, well-known teacher and author of the seminal work, Be Here Now, has described himself as a Hind-Ju. When my old friend Eddie Greenberg started speaking to me about Allah between bites of a corned-beef sandwich, and calling himself a Jufi, I knew something very odd was going on.

The late Rebbe/minstrel, Shlomo Carlebach, once explained it this way: following the atrocities and horrors of the Holocaust, not only were so many learned Jewish sages killed, but the surviving teachers and rabbis had so much death and despair to deal with that in their collective mourning they had little inspiration or enthusiasm left over with which to attract young, Jewish spiritual seekers to their own tradition, and so we all turned elsewhere in our quests for meaning, and found it in other religions and spiritual paths.

Along the way, people like Shlomo and his colleague, the late Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi of blessed memory, and many others, would make it their mission to breathe life, spirit and joy back into the Jewish world and begin to draw Jews back toward their roots to reveal and recover the unfathomed beauty and mystical riches buried in their own religious backyards. My decades-long friends and colleagues, Rabbi David and Shoshana Cooper, having immersed themselves deeply in both the Buddhist meditative tradition as well Jewish Kabbalistic studies in Jerusalem for eight years, combined the two and introduced a contemplative approach to the American Jewish world that continues to be evidenced today in silent Jewish meditation retreats offered around the United States.

But for many Jewish seekers, the timing was off; they had already fully embarked on other paths and found them powerful, useful and rewarding, and there would be no turning back. Teachers with names like Kornfield, Goldstein, and Salzberg would pioneer the practice of Buddhist Vipassana meditation around the country, sustained and growing to this day, now slipping into the mainstream under the rubric of “mindfulness.” Ram Dass drew thousands of people, many of them Jewish, into the world of Hindu deities, cosmology and a style of devotional chanting (“kirtan”) that has since been popularized by yet another Jew, known to the world as the Grammy-nominee, Krishna Das. “Jews for Jesus” and the “Hebrew Christian” movements represented an even more peculiar combining of faiths. My therapist at one point was a Jewish Sikh, complete with white turban. One way or another, it was all Jews, all the time; just not much in the way of actual Judaism.

Which brings me to the infomercial portion of this piece:

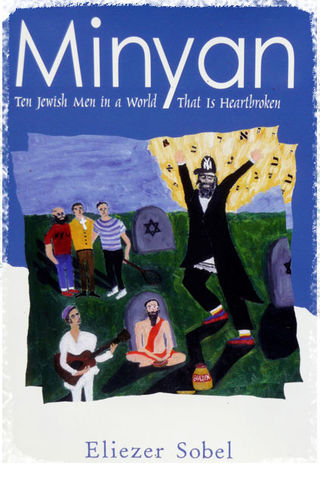

We have been called “The People of the Book,” so naturally, the way I tried to make sense of this phenomenon was to write a book, a semi-autobiographical novel about ten middle-aged Jewish guys in New York, passionately searching for God, women, and a decent, lean brisket, though not necessarily in that order. One of them is a born-again Christian, the others a Sufi, a New-Ager, a Hindu, an atheist, a Baha’i follower (who enters and departs the novel on page one, already dead, so I didn’t have to research that one), an eccentric Rebbe who’s a cross between Groucho Marx and the Baal Shem Tov (founder of Hasidism), a sports fanatic (with a religious devotion to Willie Mays), and a fictionalized version of myself as a struggling Jewish soul, looking for my roots amidst the superficial miasma of contemporary American life, lived against the backdrop and terror of being raised by a Holocaust survivor.

Titled Minyan: Ten Jewish Men in a World That is Heartbroken, the book was described by one reviewer as “Seinfeld with meaning, humor with tragic bite, sorrow with one-liners…” and by another as “…not for a Jewish audience only.”

Minyan was published in hardcover by a University press, at the daunting price of $32; my own mother told me she would wait for the paperback. Alas, she had to wait a long time, and now, in her 16th year of Alzheimer’s, I’m afraid she is long past her reading days. Nevertheless, it is now available and affordable in paperback at Amazon, and also as a Kindle, Nook & iBook. (I am 63, old-school, and a bit slow on the uptake with the whole digital e-book thing.) So go to www.minyanstory.com now, and tell all your friends!

Infomercial over. And now back to our regularly-scheduled blog:

My friend Eddie is known to his Sufi friends as Nasrudin; prior to that, Swami Muktananda dubbed him Kanaka Das; before that, we attended a New Age workshop together in which we took on new names for the weekend, reflecting our highest aspirations. Eddie became “Gentle Soul” and I can attest, he is definitely a very gentle soul. I became “Crescent Jewel” but I can’t back that one up with any clear-cut evidence. (In the advanced version of that workshop, all of the participants wore nametags that said “God.” Now that was an interesting experiment.)

Underneath it all, though, in his kishkehs, meaning his guts and heart and soul, I am convinced that Eddie remains Chaim Eiser ben (son of) Froim, just as I am Eliezer ben Avram Mendel. We are our father’s sons and our mother’s children, they are linked to their parents, and the Jewish lineage, like every lineage, goes back and back and back all the way to the Infinite Source, the One Original Being wearing the Primordial Nametag that says “God,” or more likely, “Mystery”; and that One Whatever-It-Is, is neither Jewish nor religious. Nevertheless, human beings in their infinite wisdom have found that believing in their particular version of this One Nameless Presence is a perfectly good reason to murder and kill one another in Her Non-Name.

The underlying Cosmic Practical Joke many humans have fallen for is that although there are a multitude of paths up the proverbial spiritual mountain, from the slow trudge of endless silent meditation to the speedy cable car of LSD; from the Muslim’s surrender to Allah and five prayer sessions a day facing Mecca to the Christian Eucharist and devotion to the Holy Trinity; from the yogic practices of Hinduism to adherence to Jewish halacha (law); and on and on and on, nevertheless, the view from the top of the mountain, if we compare notes from among the world’s mystics from every faith who have made the ascent, is a clear, pristine, 360-degree vision of Vast Radiance, shared equally by all who attain the summit. Once one is standing in the brilliant, luminous light of the Eternal Now, the nature and details of the particular route any one pilgrim took to arrive there becomes completely irrelevant.

Although please note: I can’t help it if you bump into a lot of Jews milling around on the trails, wearing different-colored robes. It seems we are everywhere. Lately, though, at last, with the rapidly growing interest in the Jewish Renewal Movement, as well as increased passion within other Jewish denominations, more and more you may actually discover some actual Jews traveling a Jewish path to find their religious sustenance. Now how weird is that?