Anxiety

Coming Out of the Mental Illness Closet

Why do we have to pretend to be okay?

Posted September 9, 2015

Disclaimer: Despite being a blogger on Psychology Today, I am not a psychologist, and all ideas shared here are purely personal musings with absolutely nothing substantial to back them up apart from my own experience, and even that is somewhat questionable.

If you have a runny nose, a slight fever, feel a bit achy all over and generally rundown, you might casually remark to someone, “I’m a bit ill.” It’s not an earth-shaking disclosure that requires any sort of courage to mention aloud. There is no stigma attached to the fact that you are “a little under the weather.”

From the common cold to cancer, it is acceptable and within social norms to be physically ill; it happens to everyone, and nobody judges us for it. On the contrary, most people usually empathize and wish us a speedy recovery. We may beat ourselves up at times for being physically unwell; we should have eaten better, exercised more, laid off the Tootsie Rolls and Vodka Gimlets, and thus perhaps averted our current illness or general lack of physical well-being & energy.

Nevertheless, it is perfectly okay for us to have those days when physically, we are “just not ourselves.” Which, ironically, is also my personal definition of what it means to be mentally ill: I am not myself. But who exactly is this “self” that I am not being? It is the undivided identity I enjoyed as a child, and have had subsequent glimpses of throughout my life, an inner condition in which I experience myself as a fully whole, generally happy, satisfied, good-natured, cheerful, helpful, caring, loving and loveable person, worthy of my own and others’ respect.

That admirable aspect of my persona still shows up periodically, in certain situations that call him forth, such as being in a position of leadership and service, as well as in much of my writing and other creative work. Many close friends insist that they see that version of me much better than I do.

Yet in my day-to-day inner experience of being alive, my more common feeling is that “I am just not myself.” I am generally a bit under the weather, mentally. Thus, by my own definition, I am mentally ill.

It sounds a bit shocking to hear myself say that. Such a notion had never even occurred to me, until recently. My unexamined assumption was that mentally ill people were the ones living in institutions, ranting and raving and disrobing in public. They were schizophrenic, psychotic, and secured in lockdown wards.

But clearly there is a spectrum. In the realm of physical illness, I used “the common cold to cancer” scale to represent the range of possibilities. By way of analogy, then, on a mental illness chart, schizophrenia, psychosis, and suicidal despair might be akin to cancer on the “worst-case scenario” end of the spectrum. (If you are thinking that there are worse things than cancer, feel free to substitute your favorite horrific terminal disease.) Simply feeling a tad blue, on the other hand, would be the equivalent of minor cold symptoms. You can still go to work and function in the world; it’s a minor annoyance, but it is on the illness spectrum.

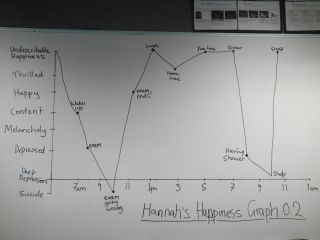

Where am I on the chart? My mental health is most often a less than half-empty cup. Like Woody Allen, I seem to suffer from anhedonia (the original title of Annie Hall), which is “the inability to experience joy.” Another diagnosis I’ve received—one of my favorites—is dysthymia, which essentially means, “Feeling mildly depressed over a prolonged period of time.” Check. Severe depression has been an accurate depiction of my inner world on way too many occasions. Suicidal ideation has occurred multiple times as well.

The bonus feeling that depressives are given—particularly in my “upper-middle” socio-economic class—is often deep shame and guilt for not being filled-to-overflowing with deep gratitude and appreciation for the multitude of blessings and good fortune that make us among the most fortunate in the world. That is to say, I am not hungry or homeless, I have all my limbs, I am surrounded by many wonderful people in my life who love me, and so forth. The implication is that I have no right to be unhappy, that mental illness for someone like me is not even permitted. Yet I am quite free to have a cold or flu, arthritis, or any physical ailment I please. Sky’s the limit.

The best that life seems to get for me is “not quite neutral”: on a scale of 1-10, on my good days I peak at 4.9, neither ecstatically joyful nor suicidal and despairing, but simply not really enjoying my day-to-day experience of existence, and always hyper-aware that there is a pit of utter resignation, deep grief, and vast hopelessness that I could tumble into at any moment, without warning. That pit is lined with fear and despair and padded with a lack of self-worth. When I hurtle down it, I hear a voice echoing up from the bottom, repeating over and over, “You wasted your life and now it’s too late.” (Note to the mentally healthy: a well-meaning “Cheer up!” or “Snap out of it!” is generally not helpful at that point.)

I haven’t even mentioned the anxiety component, which is almost always a devoted companion to depression. Suffice it to say that I can spontaneously start dripping with nervous sweat at the drop of a hat, my heart pounding and a sense of terror sitting like a brick in the bottom of my stomach. Thus, I never leave home without a hand towel and Valium, I am generally unable or unwilling to enter potentially uncomfortable social situations without a sedative, and I have been unable to sleep without Ambien for over 20 years.

Again, there is a spectrum with anxiety states: on one end there is a fairly constant but low-level sense of worry lurking in the background; on the other end are full-blown panic attacks. I’ve had the privilege of traveling all of that terrain as well.

To make matters worse, throughout all of these constantly-shifting inner mental-emotional landscapes of depression and anxiety, there is also often a great inner pressure compelling me to hide how I’m feeling and put on a public face that I imagine is presentable to the world. And more often than not, it works, and people mostly find that being in my presence is rather delightful, even when I don’t! When I reveal how I am actually feeling to anyone, they are invariably shocked, because it is not at all what they perceive. Even more astounding, they enjoy my company and continue to appreciate who I am no matter what I am feeling inside, and despite whatever I believe about myself and my deeply flawed life and character. Nobody else cares! Or agrees. Or even notices, unless I make a point of telling them.

By way of contrast, if I had a terrible cold and was constantly sneezing into a snotty tissue, I could just be in that state; it would be obvious to others that I was unwell, and there would be no inner conflict about it, no social mask required to hide it. This is simply not the case with mental illness, and it’s not fair. How then can we normalize mental illness in a similar way?

Spoiler alert: I don’t know. But it begins, I think, with this very conversation.

***

Mental illness is an illness of the mind. Life itself is never the problem, no matter what the evidence, no matter how bad it really is out there. The problem is always and only the mind, which directly generates one’s ongoing, inner experience of living, within any and all circumstances, from the unspeakably horrific to the blissfully sublime. Thus, some 40+ years ago, I began a steady regime of mental repair work. Following are the drugs for depression and/or anxiety that I’ve tried:

Abilify, Adderall, Buspar, Celexa, Cymbalta, Doxepin, Effexor, Ketamine, Klonopin, Lexapro, Neurontin, Pamelor, Paxil, Propranalol, Prozac, Seroquel, Serzone, Trazodone, Valium, Wellbutrin, Xanax, Zoloft.

These are the “mood supplements” I have used:

B12, Curcumin, D3, DHEA, Folate, GABA, Ginseng, 5-HTP, Kava, Magnesium, Omega 3s, Probiotics, Rhodeola Rosea, Saffron, SAM-E , St. John's Wort , Theanine, Tryptophan, Valerian, many others.

I've also experimented a great deal with Psilocybin (magic mushrooms), LSD, Ayahuasca, Ibogaine, Peyote, MDMA (Ecstasy), Hashish and Cannabis.

I have wired my brain daily to the Fisher-Wallace Cranial Electric Stimulator while sitting under a SAD lamp and listening to binaural brainwave sounds on headphones. The list of meditation practices, silent retreats, human potential workshops, bodywork sessions, meetings with gurus, shamans, New Age practitioners, conventional and alternative therapists, etc., is too long to write here. (It is a startling and somewhat embarrassing list, the details of which I describe with great humor and pathos in my spiritual memoir, The 99th Monkey: A Spiritual Journalists Misadventures with Gurus. Messiahs, Sex, Psychedelics and other Consciousness-Raising Experiments.)

If all the drugs and all the therapies and all the King’s men can’t put Humpty Dumpty together again, what’s a person to do? One would think I’d give up. Or do I really still believe there might be something out there that will help me just feel better? Merely to bump myself up from a 4.9 to a 5.1 would be a huge leap, because anything over 5 no longer qualifies as mentally ill. It’s the difference between being fundamentally “not okay” and fundamentally “okay.” It can be a very subtle shift, but it changes the entire universe. In only two decimal points, the lens through which one views life alters from varying shades of gray to a hint of rose. Suddenly, life is in color again. As the late Colin Wilson once put it, “Life is no longer a problem that needs to be solved before we start living.”

So no, I haven’t given up. Just as plants lean toward sunlight, “All sentient creatures,” the Buddhists tell us, “seek happiness.” We can’t stop the process. As long as blood is coursing through our veins, we remain on a perpetual correction course toward ever-greater degrees of wholeness and healing of body, mind and spirit. That’s just how we are wired.

***

As I reread everything I’ve disclosed here, it occurs to me that a reader might conclude that I actually have come down with a pretty bad case of mental illness. It’s certainly more serious than feeling a bit down and out for a few days. This is no runny nose or sniffles; this is more akin to a chronic fatigue syndrome of the mind, bordering on influenza of the soul. And yet not one of the myriad mental health professionals I have seen over the years ever once suggested that I was mentally ill. Nor would a single person in my intimate or extended circle of friends or family ever, in a million years, describe me as mentally ill. Isn’t that odd? It seems odd to me.

Mentally well people, while still susceptible to the inevitable vicissitudes of the human condition and its attendant suffering, are much more likely to find themselves, at any given moment, in a state of relative ease; they have frequent moments of quiet joy and peacefulness, and are not overly worried about anything or concerned about the future.

They are essentially untroubled—meaning, on a fundamental, essential level, at the very core of their being, they are truly “okay,” as distinct from the mentally unwell whose center of gravity is consistently “not okay.” The mentally well are able to deeply enjoy and take pleasure in the simple things of life and nature; they are generally in good cheer, and often experience a conscious gratitude for the wonderful, loving people in their lives; they notice and count their blessings as a matter of course, and they have an innate appreciation for the inherent value of life and being alive. I actually know people like this. To me, they appear to be from a different planet, and they are seeing and experiencing a radically different world. Beauty truly is in the eye of the beholder, and therefore the mentally ill have severely impaired beholding skills. We literally are not seeing properly.

There are ways to correct our vision, but that is not my subject here. I am simply pointing out the additional social pressures our society unwittingly puts on those of us with mental/emotional afflictions, via the unspoken expectation that we keep it to ourselves, or save it for our therapists. For the rest of the world, the only proper response to “How’re you doing?” remains, “Fine, and you?” God only knows what difficult and complex personal sufferings lurk behind at least 50% of every “Fine, and you?” we hear from people every day.

I once heard a self-help speaker named Stewart Emery respond to someone’s query as to the meaning and purpose of life by saying (imagine an Australian accent, a crackling sense of humor and a twinkle in his eye): “Well…I don’t know what the purpose of life is, but I know FOR SURE it isn’t to have a bad time.”

I never learned that lesson; I haven’t really had a very good time here, for the most part. But what did you expect from someone who is mentally ill?