Cognition

The Art of Thinking Well

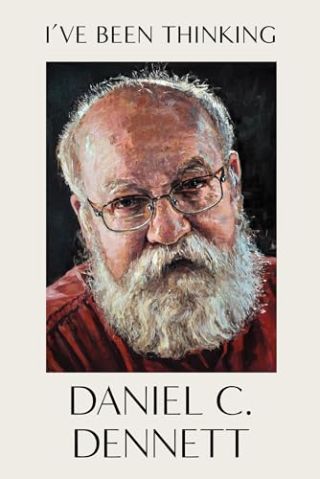

An interview with Professor Daniel C. Dennett.

Posted December 8, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Daniel Dennett has devoted much of his career to learning how to think well.

- One key among others is knowing the right questions to ask.

- He describes a strategy, Rapoport’s Rules, for winning over your opponents.

I first encountered Daniel Dennett’s work in an undergraduate philosophy class. I read his Consciousness Explained, a massive, groundbreaking book that demolished everything I knew about the nature of consciousness.

Since then, I’ve often taken pleasure in reading his works on the evolution of the mind, the birth of religion, how the brain creates thought, and how free will can exist in a mechanical universe. What strikes me most is his ability to expose and root out the false and limiting beliefs that throw even the best thinkers off track. I spoke with Professor Dennett about how to think well about hard problems.

Justin Garson (JG): You’ve pondered issues like how consciousness arises in the brain, free will, the birth of religion, and the nature of personal identity. But you've also written about how to think well. You already had one book on the subject, Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking, and I read your most recent book, I’ve Been Thinking, not just as a memoir but as a manual on how to think well. How did you come to be so preoccupied with good thinking?

Daniel C. Dennett (DCD): I got the idea from seeing what I thought was a lot of not-so-good thinking by very clever people. And I think that amazingly smart people can get trapped in ways of thinking that just lead them deeper into the weeds and farther away from insight. As I've often said, philosophers are better at posing good questions than answering them. And you need good questions. Sometimes philosophers waste whole careers on bad questions [laughs].

JG: One of my favorite lines in I’ve Been Thinking is where, in describing a key to your success in philosophy, you say, “I got used to being surrounded by people who knew a lot more than I did.” That might seem like common sense, but strangely enough, it’s not how philosophers are trained to work. How did interdisciplinary collaboration become such a crucial part of your work?

DCD: I decided that I wanted to be a philosopher because I wanted to know how the mind worked. But then I realized you can't know how the mind works if you just do philosophy. You have to learn how the brain works. You have to learn what psychologists have learned. You have to learn how computers work [laughs].

And clearly, if you tie both hands behind your back and just do philosophy, you won't make any progress. If you look at the philosophy of mind that was done back in the 1950s and 1960s, there's basically no progress at all except for, I think, [Oxford philosopher] Gilbert Ryle’s lambasting of the “ghost in the machine.” That, and [Austrian philosopher Ludwig] Wittgenstein's wonderful later work, which I think a lot of Wittgensteinians don't appreciate.

JG: I'm not sure the younger generation of philosophers always appreciates how much you've impacted how we do philosophy today. In the 1950s, if you were a philosopher trying to understand how the mind works, there was no expectation that you needed to know anything about how brains work, how evolution works, how biology works, computer science, robotics, and so on. Today, that would be almost unthinkable.

DCD: I think that's right. I think that’s been a sea change and all for the good. The retrograde pockets of old-fashioned philosophy of mind, well, I don't know who pays attention to them aside from themselves. But it’s a dwindling exercise.

JG: Could you give me an example of your favorite thinking tools?

DCD: I'll give you two of my favorites. One's very simple. It's the “surely alarm.” Whenever you see the word “surely” in a philosopher's argument, a little bell should ring—ding!—because whatever follows the “surely” is often the weakest point in the argument. It's a point that doesn't go without saying, the author feels the need to say it, but the author wants to avoid having to argue for it! It’s a dead giveaway. So, I train my students: when you see the word “surely,” a little bell should ring [laughs]. So that's the surely alarm.

The other one is Rapoport’s rules [after social psychologist Anatol Rapoport]. They are an antidote against refutation by caricature [in which you try to win an argument by presenting a simplistic version of your opponent’s point of view.]

Rapoport’s first rule is: Attempt to express your opponent's view so well, that your opponent says, “I wish I'd thought of putting it that way!” Now, that's a tall order, but you can strive for it, and then sometimes you can succeed.

Second, point out anything that you and your opponent agree about that a lot of thinkers don't.

Third, point out anything your opponent has taught you or that you've learned from your opponent that you weren't persuaded of beforehand.

Only after you've done those three things, you say a word of criticism, at which point your opponent is all ears [laughs].

You’ve shown your opponent that you're smart enough to understand what they’re trying to do. You've been smart enough to learn something from your opponent, and you agree with your opponent against those other folks. I actually school my students on using Rapoport’s rules.

JG: One last question. I often fear that our contemporary “publish-or-perish” model in American academia is going to have a stifling effect on some of our best thinkers. Your first really significant publication was a book, Content and Consciousness, which helped to bring about a reorientation in which neuroscience became central to solving problems in philosophy. Today, graduate students are expected to churn out short publications at a rapid pace, in a system that rewards small, incremental advances to our knowledge base, rather than deep, systematic thinking. Institutionally speaking, how can we protect and nurture our best thinkers?

DCD: I don't know. It's a hard question, and it's a good point to make. I didn't have any choice [laughs]. I sent around a dozen versions of a couple of chapters of Content and Consciousness to journals and got them all rejected. So, I thought, I’ll have to tell a whole big story. If I can't do that in a journal article, I'm going to have to write a book—just take my chances.

And I dare say there will be people in the future who will feel that way, and they'll do it. And some of them will win big and some of them will lose big. Life is risky. But I don't think I would encourage a graduate student to start off with, you know, their magnum opus [laughs].