Family Dynamics

Revisiting a Medical Mystery

A new book explores the Morlok quadruplets, all diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Posted June 13, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- By their early 20s, all four Morlok quadruplets were diagnosed with schizophrenia.

- Their story reveals more about shifting perspectives in psychiatry than the nature of schizophrenia.

- It also points to our changing understanding of family dynamics in mental illness.

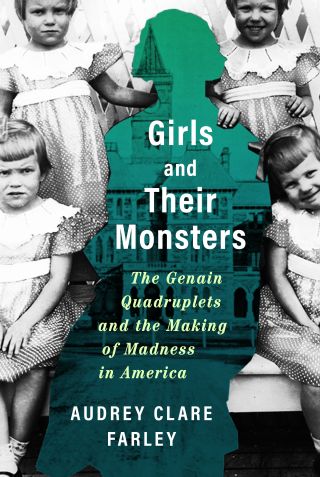

A new book, Girls and Their Monsters: The Genain Quadruplets and the Making of Madness in America (Grand Central) explores the fate of the Morlok quadruplets, born in Lansing, Michigan, in 1930. All four were diagnosed with schizophrenia by their early 20s.

A research psychiatrist gave them the pseudonym “Genain” in a published study.

Although newspapers described them as a perfect family, the book gives us a glimpse into the terror they experienced at home due to an abusive father. In some ways, the Morlok quadruplets reveal less about the nature of schizophrenia and more about our shifting interpretations of it.

The author of the book, Audrey Clare Farley, received her Ph.D. in English at the University of Maryland and also wrote The Unfit Heiress (Grand Central) in 2021, on the legacy of eugenics in the United States.

Turbulent Childhoods

From the moment of their birth on May 19, 1930, the Morlok quadruplets became national celebrities. The Lansing State Journal, in fact, ran a public competition to name the girls. The competition’s winner chose Edna, Wilma, Sarah, and Helen because it made the same acronym as the Edward W. Sparrow Hospital where they were born.

Their mother, Sadie, was the ultimate stage mother. She dressed them identically, but for different-colored bows, so their teachers could tell them apart. She also took them on tour where the girls sang, danced, and told jokes. She often referred to them collectively as “her only child.”

The book pulls no punches in documenting how their father, Carl, terrorized the family. He physically and sexually abused the sisters, particularly the youngest, Helen. He became increasingly obsessed with the idea that he needed to protect them from the outside world, and particularly from boys. By the time they were teenagers, he would often sleep with a gun by his pillow.

In the book's most harrowing scene, Carl arranged for Helen and Wilma, then 12, to have clitorectomies, due to what he saw as their compulsive masturbation. (At the time, the procedure was performed on girls considered to be “over-sexed.”) It’s hard to imagine that his abuse didn’t play a role in their mental health problems.

A Spreading Sickness

In the early 1950s, Edna was the first of the sisters to be diagnosed with schizophrenia. She began hallucinating and experiencing mysterious bodily pains. Wilma shortly followed. She became convinced her coworkers were after her.

In early 1954, Sarah developed hallucinations and delusions and was also diagnosed with schizophrenia. At the end of 1954, Helen began hallucinating and was diagnosed with catatonic-type schizophrenia.

In 1954, David Rosenthal, a research psychologist at Johns Hopkins University, became aware of the sisters and referred them to the fledgling National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in Bethesda, Maryland, where researchers thought that careful study would illuminate the origins of schizophrenia. (Soon after referring them, Rosenthal joined NIMH himself.)

From 1955 to 1958, the sisters lived at the National Institutes of Health’s Clinical Center, where they were studied intensively by psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and other experts. Their parents were studied, too. After they left, NIMH researchers continued to study them intermittently for the rest of the century. The last major report was published in 2000.

Today, only Sarah Morlok survives. She provided Farley with information for the story and also wrote her own memoir, The Morlok Quadruplets, in 2015.

Clashing Interpretations

One of the book’s themes is that, in some respects, the Morlok sisters reveal more about the changing landscape of psychiatry in the 20th century than about the nature of schizophrenia.

In the 1950s, psychiatrists often explained schizophrenia in terms of unhealthy family dynamics: the so-called “schizophrenogenic” parent. In the mid-1950s, the Morlok sisters provided plenty of fodder to those researchers who believed that schizophrenia was a result of poor family dynamics.

But, by 1963, the publication year of David Rosenthal’s massive study, The Genain Quadruplets: A Study of Heredity and Environment in Schizophrenia, the focus was largely shifting to faulty genes. Perhaps their schizophrenia wasn’t merely due to their formative environment but to genes passed down from their father.

Researchers, most prominently Seymour Kety of NIMH, sought to identify the genetic causes of schizophrenia by analyzing large data sets of family records. For people like Kety, schizophrenia was best seen as caused by a genetic vulnerability that’s triggered by a dysfunctional environment.

By the 1980s, thanks in part to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, researchers had shifted their attention to supposed chemical imbalances in the brain to understand serious mental illnesses like depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

In 1981, neuropsychologist Allan Mirsky replaced Rosenthal as head of the adult psychology lab at NIMH. A product of his generation, he was far more interested in hypothetical chemical abnormalities in the sisters’ brains than in their genes or their formative environment.

Revisiting the Family

To me, one question the book raises is this: How should we think well about the role of family dynamics in schizophrenia?

On the one hand, we don’t want to fall back into blaming parents for their child’s schizophrenia. On the other, we don’t want to ignore family dynamics or marginalize them as mere “environmental triggers for a genetic vulnerability.”

As I’ve written here, innovative recent research is starting to suggest that, while families don’t cause schizophrenia, the way the family interacts with the schizophrenic person can help, or hinder, recovery.

Whatever the future holds, Girls and Their Monsters is a powerful book that should provoke deeper reflection on how we come to grips with madness.