Psychology

Psychology and the Silver Screen

A Personal Perspective: Overcoming wounds of interpersonal racism.

Posted October 10, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

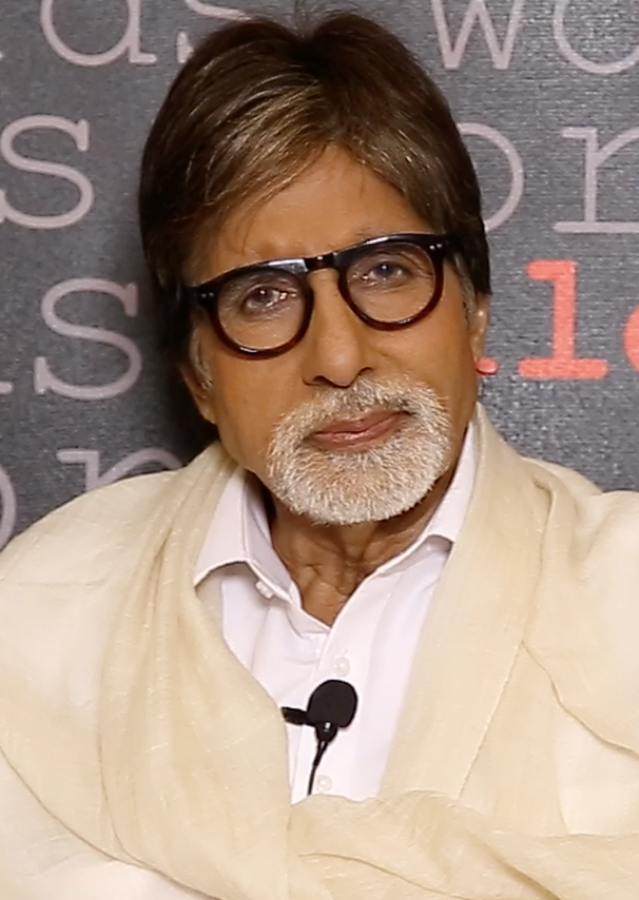

If you come from, have spent time in, or have befriended or loved anyone from South Asia, you are probably familiar with this name: Amitabh Bachchan.

Amitabh Bachchan is an Indian film industry megastar who likely has one of the most recognizable faces and voices in the world. A living legend who, this week, turns 80 years old.

I spent a fair chunk of my own childhood, as a British-born girl of Indian ancestry, watching Mr. Bachchan’s films. I grew up in a modest, immigrant household in the class-obsessed, and often “in-your-face” racist, Great Britain of the 1980s. Families like mine represented the millions of brown and Black immigrants who poured into Great Britain, from all over its former colonies, as legal citizens who were recruited to fill post-World War II vacancies. They became factory workers, janitors, bus drivers, postal workers, worker bee doctors, teachers, and small business owners.

At its peak, Great Britain’s Empire was the largest in history, ruling over almost half a billion people and spanning a quarter of the Earth’s total surface.

British colonial rule was also often ruthlessly entitled. They oppressed their colonial subjects' human rights and ignored their suffering sometimes with colossal negligence. Though they were called “members of the empire,” colonial subjects were not afforded the same rights as their white counterparts.

It was perhaps this traumatic history that explains why I have always felt I was born into two worlds. In the first, Great Britain was my meritocratic savior, rewarding hard work and dedication with a life of opportunity and promise. In the second, Great Britain was seething with racial tensions and my brown skin and Indian heritage meant my citizenry was second-rate.

Inferior. Dirty. Stupid. Uncivilized. Throughout my childhood, this was my experience of how some white people viewed British South Asians. As a child, I routinely witnessed my parents being given scornful service in shops and restaurants and having their accented English mocked within earshot. It was not uncommon for a walk to school, a trip to the park, or a family outing to the seaside to be marred by a racist incident: a young white man spitting at us, a gang of skinheads hurling racial threats, or some random person offering unsolicited (and hateful) advice, “You should all go back to where you came from!” I still vividly recall an incident in a local grocery store where my sibling, who was barely 3 years old at the time, was flipped over in her stroller. The culprit? A white boy, age around 10, who yelled a racist slur as he fled the scene, leaving my bewildered mother scrambling to comfort her bawling baby.

Our family Bollywood movie nights represented a haven of sorts. In a tough immigrant life, this activity was the epitome of leisure. It was one of those rare occasions when I’d see my parents—at least the younger version of themselves—truly carefree, laughing out loud, engrossed in content, and entertained together. When I was growing up, Amitabh Bachchan was everyone’s favorite movie star and grabbing the last VHS copy of one of his movies from the local Indian video rental store was considered a triumphant act.

As I grew older, I had less and less time for Bollywood movies. To be honest, many of the plots and images and storylines I binge-watched, as a child, would not hold up well in the 21st-century light of day and for decades this medium would occupy a smaller part of my life. That was until the 2016 United States presidential election. Now, I was a naturalized U.S. citizen and while I was not naïve to the ongoing presence of societal racism, in 21st-century America, I was stunned by the tsunami of vile occurrences I was witnessing. All the progress that had been made, in my lifetime, on matters of race, identity, and belonging appeared to be unraveling at warp speed.

Shortly after the election, I found myself developing a curious compulsion. I would search the internet for clips of Amitabh Bachchan movies I grew up watching. I’d steal hours watching this content because it replenished and comforted me in a way that I could not explain in words. The psychiatrist in me could not help but wonder why.

The diagnostic bible used by mental health professionals, all over America, to diagnose PTSD requires the survivor to have experienced a “Trauma with a big T” type of event, such as surviving a deadly housefire, a rape, or being robbed at gunpoint. In recent years, there has been growing criticism from mental health professionals and scholars that this conceptualization of trauma and PTSD fails to encompass the negative impact of oppression on the mental health of its survivors. Oppression, in this context, is defined as:

“a state of asymmetric power relations characterized by domination, subordination, and resistance, where the dominating persons or groups exercise their power by restricting access to material resources and by implanting in the subordinated persons or groups fear or self-deprecating views about themselves.”

Scholars argue that the current requirement for “Trauma with a big T” events being integral to making a diagnosis of PTSD excludes the damaging impact of more insidious (yet frequent) “trauma with a small t” events that are integral to such experiences of oppression.

Who is oppressed, in our society, is often inextricably intertwined with identity, e.g., gender, race, sexual orientation, class, or ability. We know that understanding the impact of oppressive forces is complicated, because oppression plays out on various levels from the intrapersonal to the interpersonal and extends to the societal (e.g., via the dehumanizing of victims of oppression) and even global level (e.g., via colonialization or exploitative economic systems).

While contentious debate continues to rage about whether oppression-based PTSD exists, what is irrefutable is the overwhelming body of data documenting the psychological harm (e.g., low self-esteem, depression, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse) of oppression on members of marginalized communities.

It dawned on me that watching Mr. Bachchan’s movies in my childhood extended far beyond a harmless way to pass the time or an act of immigrant escapism. His movies were proactively medicating my psychological wounds that resulted from daily exposure to subtle (and not so subtle) acts of race-based oppression. I was submerged in a world where my skin color and heritage were completely undermined by the wider society and culture.

South Asians had lived in Great Britain for centuries, yet I was much more likely to see them cleaning airport toilets, driving minicabs, or as servers in a restaurant than in a position that commanded respect, power, or influence. Bias was baked into the organizations and institutions of the country of my birth and my childhood was playing out, in the shadow, of a violent colonial past. A past that implied that everything white—be it white behavior, white thought, or white actions—was superior to anything I could ever be.

Now, in my American life, those old wounds had re-opened and, as if on autopilot, I’d returned to the movies of Amitabh Bachchan in search of the same validation and solace I must have unknowingly absorbed as a young girl.

Today as an adult when I re-watch his movies, it is clear the lessons his artistry was conveying to me.

Mr. Bachchan is perhaps most famous for his portrayals of angry young men. These characters were survivors of unspeakable childhood trauma. In his movies, he was an angry badass often fighting for justice and rebelling against the establishment and righting wrongs by any means necessary. These stories contrasted with the more common representation of brown people I saw during my childhood: Brown immigrants were expected to be meek and servile. Passively accepting of their fate, whether it be good or bad.

What Bachchan’s movies allowed me to internalize as a child: Brown people have permission to feel

Mr. Bachchan played a variety of protagonists. These characters practiced different religions, spoke various languages, and were poor, rich, educated, or illiterate. The style of his roles could vary from comedic to action hero, from serious intellectual to romantic lead. His characters were also psychologically complex and able to express the darker aspects of themselves. These movies contrasted with the dehumanized and bland stereotypes of brown people that populated the Western media of my youth.

What Bachchan’s movies allowed me to internalize as a child: Brown people are multidimensional and heterogeneous

Perhaps what I love most about Mr. Bachchan’s performances is his ability to appear completely at ease with his character. Whether he is playing the life and soul of a party, a fearless action man, a sophisticated style icon, an introverted writer, or an arrogant rich businessman, his portrayals come with unapologetic ease. Unashamedly visible. Such ease was at obvious odds with my perceptions of the average brown people of my British youth. An awkward, invisible minority responsible for doing the back-breaking, anonymous work that kept British towns and cities churning yet rarely allowed a seat at the table.

What Bachchan’s movies allowed me to internalize as a child: Brown people are cool

Mr. Bachchan played a variety of roles where his brilliance was not only accepted but embraced. His characters included a rock star, an award-winning playwright, a beloved poet, a successful architect, a talented doctor, and a fearless policeman. His characters could be brash and arrogant, but none of this took away from his brilliance. As a brown girl, I’d frequently be signaled to “know my place,” and had accepted that I would have to work twice as hard to get half as far in my life. When performance takes place under the colonial gaze it is important to not outshine your white counterparts. Humility and, ultimately, subservience were what was expected from me.

What Bachchan’s movies allowed me to internalize as a child: Brown people are brilliant and should never dim their light for anyone

In his hundreds of movies, Mr. Bachchan wooed many different heroines. His heroines were all brown women. Some were short, others tall, some were thin, others had fuller figures, some were light-skinned and others had darker complexions. Regardless, his characters loved them all. Moreover, the characters of these heroines were intelligent, independent, and feisty. Growing up, the dominant standard of what it meant to be beautiful rarely encompassed traits common to brown women. Also, it was rare for me to meet brown women who were fearless and had agency; instead, servility and suffering were the characteristics that brown women were more likely to be revered for.

What Bachchan’s movies allowed me to internalize as a child: Brown women are beautiful

It has been more than 40 years since I started watching Amitabh Bachchan movies, as a young girl in my parents' living room. It’s high time I take this moment to put pen to paper and express deep gratitude for the remarkable work of a truly legendary artist. His tremendous talent helped me (and likely a whole generation of brown diaspora children) heal from the traumas of race-based oppression. Happy 80th Birthday to Mr. Amitabh Bachchan.