Mental Health Stigma

The Shift to Knowing the Mental Health of All Your Students

Personal Perspective: Some counseling centers want to know and others do not.

Posted March 6, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- There are two main camps of campus counseling directors regarding data collection on student mental health.

- Some don't want to know, and some do—legitimate reasons for both camps.

- Imagine a world in which we map mental health the same way epidemiologists do medical illnesses and viruses.

There are two camps of campus counseling center (aka CAPS) directors:

- Those who do not want data on how their students are doing and

- Those who do.

This is obviously a simplified take on an exceptionally complex web of ethical, legal, moral, and practical considerations when it comes to campus mental health data in the U.S. And that's the focus of this piece: mental health data. It's critical to call out that, without exception, 100% of the campus mental health leaders I've ever spoken with care deeply and passionately - with the devotion of guardian angels - about the students at their respective schools. No exceptions. No buts.

Still, confoundingly, there is a contingent who do not want to know how their full student body is doing. Why wouldn't mental health campus leaders want to know the real-time data on how their students are doing?

The Plausible Deniability Camp

There are legitimate reasons. The first is legal. Liability is a genuine concern for offices of legal counsel. Schools get sued somewhat frequently. And legal counsel exists to mitigate risk. Thus the push for plausible deniability. The logic is that as long as counseling centers don't know, they can't be held liable.

Counseling centers also self-regulate by the code of ethics. It's not the same mindset that their legal advisors insist upon. However, counselors have a duty to warn, also known as the duty to protect in California, if they know of a threat. So, if we know, we must act.

As such, legitimate reason No. 2 for ascribing to the first camp is resources. Even though most mental health data is not crisis-related, it's a Pandora's box to have real-time mental health data of all your students just sitting around. What are the (positive/negative) consequences of such insights?

We know that the number of sick people is well beyond the counseling center's resources to be able to serve.

Sixty percent of those who are diagnosed with mental health illnesses do not get support. And that's for those who are diagnosed. The number who may need support is likely magnitudes higher than the 9% of students on larger campuses (>30,000 students) to 18% on smaller campuses (<2,500 students) who are able or willing to utilize campus mental health resources (utilization data from the AAUCCCD annual report).

Campus counseling centers are already overburdened when serving less than 9-20% of their students. They also sense from the macro data from the CDC, the U.S. Surgeon General, and elsewhere that the other 80-91% aren't doing all that great.

These are strong arguments for not wanting to know. But what about the other side of the liability and duty to warn coin? Specifically and intentionally avoiding data for the sake of plausible deniability doesn't feel right either.

Full Visibility Camp

What are some reasons why counseling centers would want to know how their non-help-seeking students are doing?

This is a novel concept in mental health: ethically exposing or publicizing all mental health data.

The entire field is premised on patient data staying locked in a vault, restricting it to patients and their care providers. All health care functions this way; though, much more epidemiological data is available for medical versus mental health.

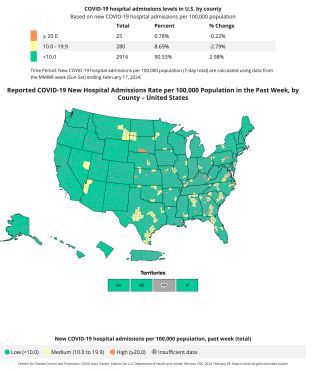

Another analogous way of thinking about the issue of vaulted mental health data is what do we do, as a society, when we have and use the epidemiological data on influenza or COVID or if an outbreak of measles is identified? Epidemiologists and medical professionals map it. Then, they use the maps to make decisions about vaccinations, mandates, quarantines, and other actions to directly combat the deadly threat of viruses and other illnesses that threaten societal health and well-being.

Imagine the impact of knowing, publicizing, and mapping real-time, anonymized mental health data of an entire campus. What would you, as a mental health professional, do with such insights on your campus, base, or organization?

You might:

- Leverage the data to go to the mental health hot spots on campus proactively

- Leverage the data to be "force multipliers" by activating cross-campus partners (peer mentors, outreach teams, group therapy sessions in the specific buildings or areas flashing red, etc.)

- Leverage the data to create more targeted outreach interventions by groups

- Nothing. Intervention isn't always necessary. Sometimes, students (all of us) just want those around them to know and have an empathetic response from a friend (not a counselor).

Getting the Data

But how could we possibly know how the other 80-91% of our students are feeling?

Unlocking mental health data and releasing it from the vaults of secrecy is what VEXT does. [Disclaimer: I am the CEO of VEXT and VEXT has a related patent on this concept.] Students share their real-time mental health data via the VEXT app. VEXT anonymizes and aggregates the data for students and counseling centers via the VEXT counselor console dashboard.

In other words, VEXT jail breaks mental health data (with very clear terms and user consent) to map it and make it public how all students are feeling, especially those who are not exhibiting help-seeking behavior.

In my first Psychology Today post I shared that "[students] expect that someone around [them] should already know how we're feeling."

It's reasonable to assume that these same students would be disappointed to learn that campus mental health leaders are intentionally avoiding—even if for very good reasons—knowing how they're feeling.

Knowing What the Other 90% Feel

In a recent personal interview with members of the Center for Collegiate Mental Health, they referred to this other data—the data from those who do not seek help or go to campus mental health services—as the "holy grail" of mental health data. (This is/was not an endorsement of VEXT by CCMH.) Of all the hundreds of thousands of sessions across CCMH's 800-plus member schools, they have a trove of data for students who go to counseling centers. But data on the other ~90% is non-existent.

How does that ignorance impact practice? If we rely only on the intake forms of those who come to our centers as the full story, what are the impacts on the majority who do not?

As a counseling center therapist or director, if you could have data on all your students, what would you do with it?

Is it better to know or not know?

Shouldn't we want to know?

References

Thomas Insel, MD (2022). Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health. NY: Penguin Press.