Memory

Why America Still Can’t Read

America can’t read because we aren’t teaching English spelling.

Updated May 23, 2024 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Spelling is essential for reading and writing according to brain imaging and neuroscience.

- Decades of flawed whole language/balanced literacy in teaching spelling led to failing reading scores.

- Spelling books and current neuroscience-backed strategies for teaching reading can improve reading scores.

Nine years ago I published a post entitled “Why America Can’t Read.” It proved to be a hot topic. In spite of what many consider herculean efforts, reading scores have not improved over the last nine years based on the National Test of Educational Progress known as the “Nation’s Report Card.” In fact, scores have remained flatlined and in schools with struggling students, scores have dipped below pre-COVID levels (Goldstein, 2023). As reported in the 2017 post, a missing piece of the puzzling lack of progress is based on the crucial role of spelling in the brain for reading.

In the 2017 post I critiqued the major popular whole language/balanced literacy reading programs that have failed largely due to their inadequate and haphazard delivery of spelling instruction (Gentry, 2017; Swartz, 2019). Schools where English spelling is not being taught explicitly will continue to have many students who struggle with reading as they do today.

Why the Brain Needs Spelling for Reading

Neuroscience makes a compelling case supporting spelling for reading. Take for example the work of France’s world-renowned neuroscientist Dr. Stanislas Dehaene whose 30-year career in neuroimaging continues to illuminate how the brain learns to read. He speaks and writes eloquently about how the brain reads (Dehaene, 2009). Dehaene explains that reading is a visual coding system for mapping to one’s already existing spoken language to create meaning. You can’t read without activating your memory of spelling images in your brain. See this Psychology Today post by Ralph Lewis on the neural basis of what constitutes memory including spelling.

To write a message you use the same system, they are two sides of the same coin. You use the spoken language in your brain to compose a piece with words. Without English spelling stored in your long-term memory, you can’t write in English. Humans are born with circuitry for learning to speak but no one is born with circuitry for literacy. Since English spelling is at the very core of the reading/writing brain, this complex orthography should be taught explicitly to all learners of English.

Why educators should put spelling books on a pedestal

Spelling books are essential tools for optimal teaching of reading and writing. Noah Webster knew this in 1783 when his first American reading textbook was published to phase out the use of British spelling books for teaching reading in America. Webster’s first reader, popularly referred to as the “Blue-backed Speller,” sold over 80 million copies over the next century. Using a spelling-to-read method, Webster is credited with teaching America to read and being the founding father of American education. Three decades of whole language/balanced reading theory dating back to the 1990s denigrated spelling books, forced teachers to pull them off the shelves and replaced them with failed delivery systems for teaching spelling still found in many classrooms today (Gentry, 2015, Swartz, 2019). We need to bring back Webster’s spelling-to-read methodology and put spelling books back on a pedestal.

Why Spelling Books Work

Both in Reading in the Brain and in his keynote address at a recent Learning Ally Conference, Dr. Dehaene described five optimal conditions needed for teaching the brain to read (Dehaene, 2009). Each one of them applies directly to appropriate use of spelling books:

1. Structured Literacy

Grade-by-grade research-based spelling books are the resource teachers need to deliver explicit, systematic, teacher-guided, and engaging spelling instruction. Instruction should not be a word list that is assigned to be learned at home or drilled into short-term memory by boring rote memorization. Instruction should not rely on the problematic whole language/balanced literacy techniques that too often provide no curriculum of words for each grade level. These flawed techniques provided minimal guidance such as expecting children to “discover” how English spelling works on their own as in the discredited whole language program Words Their Way (Gentry, 2015).

Spelling books designed for structured literacy include lessons on morphology as students learn about the rich borrowing of English spelling patterns and word parts from other languages including Greek and Latin roots, and roots from other languages. Even as early as first grade the curriculum in a research-based spelling book is based largely on high-frequency Anglo-Saxon patterns which are presented in virtually all first-grade level phonics programs. These spelling lessons take phonics learning to a deeper level, not just recognition for reading but retrieval of correct English spellings for writing. Spelling book lessons include explicit instruction in lessons with harder multisyllabic words as students advance up through the grades. Children are guided in mastery of increasingly difficult base words, prefixes, suffixes, compound words and contractions all of which are first introduced in Grade 1 in a spiraling upward curriculum. English has a complex orthography and should not be expected to be picked up by osmosis from independent reading or learned without direct implementation of structured literacy.

2. A Well-Designed Curriculum

Grade-by-grade research-based spelling books provide a curriculum of English words for each week teaching the right words at the right time based on yearly developmental expectations. For example, a first-grade pretest-study-posttest curriculum consists of 20-minutes-a-day of teacher-guided lessons that begin with learning each word’s meaning, sounds, and pronunciation. This is especially important when English is not the primary spoken language at home. In first-grade level spelling books, first graders are expected to master 300+ words as brain words into long-term memory for automatic reading and writing by the end of the year. In Grade 2 and beyond mastering 20 words each week and learning their meaning and pronunciation provide a safety net. The curriculum enables a teacher to monitor each student’s yearly word knowledge progress and intervene with a small group or individual word study for children who are not reaching mastery.

3. Active Engagement

Active engagement of the child occurs during the pretest on Monday, during daily multi-sensory practice with the week’s words to secure the word’s spelling in long-term memory, and during a posttest on Friday to assess if the words were mastered or if the child needs more instruction and practice.

4. Feedback

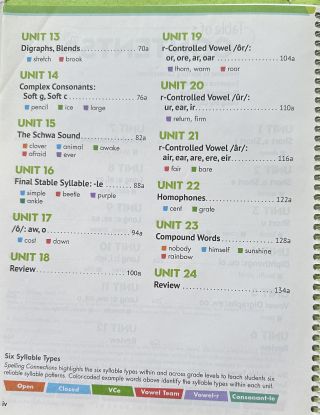

Teacher feedback in spelling book lessons enables the child to see what she or he got right or wrong and self-correct if needed. Without teacher feedback, the child may not grasp the pattern, rule, or lesson focus. Weekly lessons are very specific as illustrated in this sample of weekly third-grade units. A whole-class teacher-guided self-correction of each word makes it possible for the teacher to point out the specific word features the child is learning or missing.

5. Motivation

Motivation is a factor in any kind of learning and mastery. Good teachers are masters of motivation. Most are advocates for quality spelling instruction. They want a curriculum to make grade-by-grade instruction in English spelling comprehensive and consistent across grade levels. They want to limit the word study time to 20 minutes a day with fun, stimulating, and engaging lessons rather than having to find lessons on their own, or worry about how to shore up whole language/balanced reading resources that have failed for three decades. Not surprisingly, many of the expensive computer-based intervention programs now in use have not improved reading scores due to a lack of teacher-student interaction. Computers don’t teach and motivate struggling spellers, teachers do.

Cognitive neuroscientists now routinely report that nine out of 10 children should be able to learn to read and spell English proficiently with scientifically supported instruction which includes a spelling-to-read instructional method (see, for example, Al Otaiba et al. 2009). Teachers, parents, administrators, school boards and all stakeholders should provide spelling books in the service of better reading scores if nine out of 10 students in their schools aren’t reading and spelling proficiently. Stand against the current formidable pushback from high-ranking administrators, publishers, and reading-guru entrepreneurs who spent or raked in billions of taxpayers’ dollars over the last three decades without providing explicit spelling instruction. Developmental psychology and neuroscience now show that spelling knowledge is critical for developing the architecture of the brain’s neurological reading circuitry. In schools with struggling students, spelling books and spelling-to-read methodology are the missing pieces of the puzzle. (Gentry & Ouellette, 2024).

References

Al Otaiba. Stephanie, Connor C McDonald, Barbara Foorman, Christopher Schatschneider, Luana Greulich, Jessica Fulson Sidler. 2009.”Identifying and Intervening with Beginning Readers Who Are At-Risk for Dyslexia: Advances in Individualized Classroom Instruction.” Perspectives on Language and Literacy. Fall;35(4):13-19. PMID: 25598861; PMCID: PMC4296731.

Dehaene. S. (2009). Reading in the brain. New York: Viking Penguin.

Gentry, J. R. (2015) “Why America Can’t Read,” Psychology Today, August 25, 2015, in Raising Readers, Writers, and Spellers.

Gentry, J. R. (2022) Spelling Connections—A Word Study Approach. Columbus, Ohio: Zaner-Bloser Publishers.

Gentry, J. R. & Ouellette, G. P. (2019) Brain words: How the science of reading informs teaching. Portsmouth, NH: Stenhouse Publishers.

Goldstein, Dana, “What the New, Low Test Scores for 13-Year-Olds Say About U.S.” The New York Times, Education Now, June 21, 2023

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/21/us/naep-test-results-education.html

Lewis, Ralph (2923) “What Actually Is a Thought? And How Is Information Physical? Psychology Today, October 7, 2023, in Finding Purpose.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/finding-purpose/201902/what-act…

Moats, L. D. (2005). How spelling supports reading: And why it is more regular and predictable than you may think. American Educator, 29(4), 12,14-22, 42-43.

Swartz, S. (2019, December 3). The most popular reading programs aren't backed by science. Education Week, 39(15).

https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2019/12/04/the-most-popular-reading-…