Burnout

Physician Depression and Burnout

What’s the difference, and does it matter?

Posted December 7, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Physician burnout and depression are on the rise.

- Mental health disorders and outcomes are frequently omitted in media discussions of burnout.

- Interventions for both mental health and burnout in healthcare professionals must be considered together.

- Systemic and individual changes must be made to help healthcare workers avoid burnout and other mental health issues.

by Carol A. Bernstein, M.D.

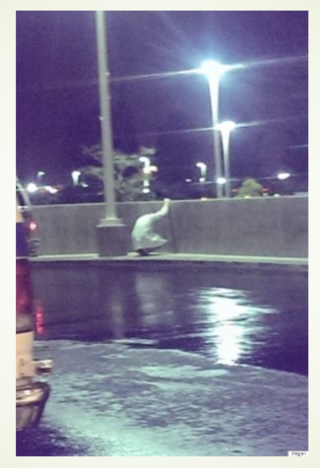

Most of us would like to view our doctors as being always strong, in charge, knowledgeable, and available. In reality, many feel like the emergency room physician pictured at left after a difficult and challenging shift.

Increasingly, the popular press has featured articles on the “great resignation,” driven by “burnout,” emotional exhaustion, and “languishing.” Both the lay press and professional journals have published articles focused on burnout and growing concerns about the mental health of healthcare providers.

While Covid played a role in this phenomenon, even before the pandemic, concerns about burnout led the National Academy of Medicine to establish the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-being and Resilience.

Burnout or Depression?

One problem with media reporting is the continuous conflation of definitions of burnout with those of depression and a tendency to confuse both systemic and individual causes and solutions of both conditions. Since the symptoms may be similar—e.g., apathy, lack of interest, difficulty concentrating, even sadness—it has been difficult to separate out whether the causes (and therefore the solutions) should be systemic rather than individual. For example, in a 2018 review of nearly 200 studies involving more than 100,000 physicians from 45 countries, 142 unique definitions of “burnout” were used, resulting in an overall burnout rate ranging from 0 to 81 percent—and that was just among physicians!

Complicating matters further, mental health disorders and outcomes are frequently omitted in media discussions of burnout. Yet, while mental health problems and burnout are, indeed, distinct, they may also be connected. Also, mental health disorders can affect anyone, and their presence in individuals is not always related to the workplace. In turn, viewing burnout exclusively through the lens of individual mental health challenges often overlooks the systemic context in which burnout occurs.

For example, studies done before the pandemic documented high rates of mental health problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, trauma, addiction) among physicians and other healthcare workers. Legislation such as the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act (HR 1667), named after an NYC emergency medicine physician who took her own life, has further highlighted the need for mental health screening, reduction of stigma for seeking help, and timely access to quality mental health services for physicians and other healthcare workers.

In other words, interventions for both mental health and burnout in healthcare professionals must be considered together since both are critical to sustaining a workforce that is able to provide a high quality of care for patients.

What are some of the systemic factors in healthcare systems that contributed to clinician burnout even prior to the Covid pandemic?

- Excess stress and fatigue from long work hours

- The intensity of the work environment

- Sicker and more complicated patients

- Pressure to get patients out of the hospital quickly

- Loss of physician autonomy and meaning in patient care

- A focus on efficiency, regulations, and metrics that inhibit meaningful clinician-patient interactions

- An electronic medical record that was designed for billing and scheduling rather than improving the nature of clinical care

Other factors include increased performance measurement (quality, cost, and patient experience), loss of control over work, inefficiencies in the practice environment, and the increased complexity of medical care.

In addition to these organizational issues, society has had to contend with a socio-political environment in the midst of a pandemic, a war, toxic political discord, economic instability, climate change, and racial injustice. Furthermore, the social isolation required by Covid protocols and the resulting creation of virtual work environments (despite their convenience and benefits) has fractured the usual benefits of social cohesion, which often mitigated the impact of similar disasters.

Into this cauldron of challenges, a significant and long overdue national discussion has been introduced regarding the importance of mental health and the stigma which prevents so many from seeking out the treatment they desperately need. However, the inter-relationship of the effects of the work environment with individual factors is complicated. The relationship is not always linear, although challenges in one area can lead to problems in another.

For example, prescribing mental health treatment alone for an individual who’s struggling to cope with a toxic work environment may be inadequate. Similarly, focusing on work-setting challenges for individuals who, in fact, are struggling with mental health disorders would do them a profound disservice. Systemic issues must be addressed systemically, while individual issues must be addressed by the individual.

What are some systemic solutions?

- Healthcare systems must rebuild a sense of community as the pandemic recedes by expanding structured mentorship and professional development programs, such as buddy and coaching programs.

- Healthcare organizations should encourage recurring social events, foster team-building activities and funded annual events, and consider the challenges and opportunities of in-person versus virtual work.

- We must promote leaders who lead by example and foster a culture of wellness, are authentic, share their own vulnerability, and speak to the values of personal and professional growth, compassion, and community.

- We must continue to work with government agencies, insurers, and regulators to reduce unnecessary administrative burdens for the healthcare team and promote innovative technology which will allow healthcare workers to return to working with patients instead of computers.

What can be done on the individual level?

- We must ensure the availability of mental health services that are confidential, high-quality, affordable, and easy to access.

- Specifically, we should make use of anonymous screening tools for burnout and depression. Such tools can be useful in reducing stigma and must be directly linked to services.

- All systems and healthcare organizations must define a clear system for referrals to individual mental health services. At present, most only offer lists of referrals either to providers or groups of providers, which rarely lead the individual to direct care.

- Institutions should have walk-in well-being centers and after-hours emergency phone lines.

- The institution of a national suicide and crisis lifeline (call or text 988 or chat online at 988lifeline.org), which operates 24 hours, 7 days a week, is an important step in the right direction.

One critical innovation would be to have a central entry point for the triage of mental health services by an experienced psychiatrist. Historically, triage functions have been relegated to the least experienced practitioners because of cost concerns. Of course, clinicians with different training backgrounds, such as psychologists, social workers, counselors, and nurse practitioners, can provide much-needed care to many people.

However, psychiatrists who understand both systemic challenges to well-being in addition to being clinically sophisticated would be best able to differentiate between issues that merit systemic interventions as opposed to those which require clinical care and should be on the front lines of determining which form of treatment is most appropriate.

If you or someone you love is contemplating suicide, seek help immediately. For help 24/7, dial 988 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, or reach out to the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.