Trust

To Trust or Not to Trust

How parents perceive children’s willingness to accept information from others.

Posted December 2, 2021 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Parents were asked to rate their children's likelihood of trusting various individuals, as well as several personality traits of their children.

- Children's conventional attitudes and rebelliousness were correlated with parental perceptions of trust.

- Importance to parents of an independent-minded child was correlated with a lower likelihood of copying a model's choice of an inefficient tool.

A good deal of research has explored the factors that influence children’s willingness to trust and learn information from new speakers. For example, Koenig and colleagues (2004) found that children as young as 3 and 4 years old selectively trusted information from informants who were previously reliable in their labeling of familiar objects. Jaswal and Neely (2006) demonstrated that past reliability was an even better predictor of future trust than age. Similarly, children in a study by Corriveau and Harris (2009) were more likely to trust familiar rather than unfamiliar informants, but only if the familiar informants had a history of accuracy.

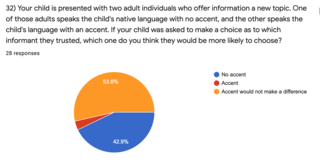

In addition to previous reliability and familiarity, another factor that influences children’s willingness to trust information from new informants is their accent. Children are more likely to endorse information presented to them by a native-accented speaker than a foreign-accented speaker (Kinzler et al., 2011).

The number of informants that agree also plays a role. Children are more likely to trust information agreed upon by a majority than information presented by a dissenter (Corriveau et al., 2009). This is also true in imitation—children are more likely to imitate actions modeled by a majority (Haun et al., 2012; Hermann et al., 2013), even if those actions are inefficient (DiYanni et al., 2015).

Survey of Parents' Perceptions

One question that my students and I had was how parents perceive the factors that affect their children’s willingness to trust (or not to trust) and their willingness to copy (or not to copy) others. We therefore designed a 34-question survey and distributed it via Google Forms to parents of children ages 3 to 6. We received responses from 28 parents of four 3-year-olds, one 4-year-old, twelve 5-year-olds, and eleven 6-year-olds (15 females and 13 males).

Questions asked about parents’ perceptions of their children’s likelihood of trusting information from various individuals (e.g., parents vs. siblings vs. strangers), parents’ perceptions of the impact of various factors on their children’s trust (e.g., gender, age, ethnic background, accent), parents’ ratings of various personality traits in their children (e.g., conventional, rebellious, introverted), and parents’ ratings of the importance of various traits in their children to them (e.g., independent-minded, obedient, rule-following).

Finally, parents were presented with two hypothetical scenarios based on an imitation paradigm in which a model intentionally elects to use an inefficient tool for a task over a more efficient one (as in DiYanni & Kelemen, 2008 and DiYanni et al., 2011). Parents were asked: “On a scale from 1–4, if your child watched an unfamiliar adult choose a tool made of fuzzy pom-poms to crush a cookie rather than a solid-bottomed one, how likely do you think your child would be to copy the model and use the same inefficient tool?” (1 = not likely at all; 4 = very likely). They were also asked: “On a scale from 1–4, if YOU as the parent were the one who modeled choosing the pom-pom tool, how likely do you think your child would be to copy you and use the same inefficient tool?”

Results

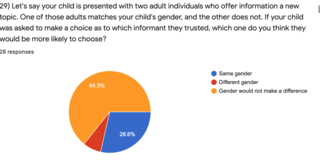

Results indicated that parents did not believe that an informant’s shirt color or ethnic background would make a difference to their children’s likelihood of trusting that informant. However, while 64.3 percent of parents said that an informant’s gender would not make a difference, 28.6 percent did predict that their children would be more likely to trust someone of the same gender. And while 53.6 percent of parents stated that an informant’s accent would not matter to their children, 42.9 percent believed that their children would be more likely to trust information from an informant with a native accent than from one with a foreign accent (in line with the findings of Kinzler et al., 2011).

Further analysis revealed that only a few variables were correlated. Somewhat surprisingly, there was no significant correlation between parental ratings of their child’s introversion or likelihood of wanting to please others and their perceptions of their children’s willingness to trust information from parents, older or younger siblings, grandparents, teachers, familiar adults, strangers, or unfamiliar authority figures. Nor were introversion or desire to please associated with parents' beliefs that their children would copy an unfamiliar adult or a parent in the cookie-crushing task.

Parental perceptions of their children’s trust of parents, older or younger siblings, grandparents, teachers, familiar adults, strangers, or unfamiliar authority figures were unrelated to the importance to parents of their children’s independence, rule-following, or obedience. Independence, rule-following, and obedience were also unrelated to parental expectations regarding their children's willingness to copy an inefficient model.

What we did find was that children who hold more conventional attitudes were more likely to trust information from an unfamiliar authority figure (as reported by their parents). This aligns with recent research suggesting that children strongly rely on conventional information to guide their learning from teachers (e.g., Clegg & Legare, 2016). On the other hand, children who were reported to be more rebellious by their parents were also reported to be less likely to trust information from both parents and teachers.

We also found that parental guesses about what their children would do in the imitation paradigm in which a model chooses an inefficient tool had a few predictors. For example, the likelihood of copying an unfamiliar adult who models the use of an inefficient tool to crush a cookie was positively correlated with their likelihood of trusting a stranger. In addition, the importance to the parent of the child being independent was negatively correlated with the likelihood of copying a parent who models the use of an inefficient tool to crush a cookie.

Important Takeaways

It is important, of course, to keep in mind that this survey is based entirely on parental perceptions, and may not parallel how children behave in reality. Also, the sample was small and may not be representative. However, there are some important takeaways from studies on trust. While open-mindedness and trust are admirable qualities and should be encouraged in children, so should discretion and diligence. In a world full of both information and misinformation, both real and fake news, and both trustworthy and untrustworthy informants, it is crucial for parents to be vigilant about those to whom their children are exposed and those to whom their children listen.

*A special thanks to Katie Candray and Tara Mason for their help in the design and distribution of this survey and in data analysis.