Play

In the Children's Eyes: Is There Enough Playtime at School?

A brief survey of pre-K to third-graders shows how much kids value play.

Posted November 1, 2021 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- With the pandemic's disruption of school, there is a concern that children need to "catch up," with a resulting emphasis on academics.

- Play remains equally important — if not more — to healthy child development as it was before the pandemic.

- Children recognize the need to play at school, and teachers should ensure that enough play time is included each school day.

For many children, the fall of 2021 brought a return to full-time education in the classroom. Although educators and administrators may be anxious about a need to catch up on academics, most developmental psychologists would agree that any young child’s school day needs to include play mixed in with their education. Frequently, academic concepts can even be presented in playful ways.

Unfortunately, however, there is a growing trend toward the reduction of recess at school (see also this report), despite evidence showing how important recess time is to children’s social and emotional development and to their attention, working memory, and behavior.

To take a pulse of how teachers and parents of young children — in preschool through third grade — feel about the role of play in education, I conducted two mini surveys. The results of the survey for the teachers were presented in my August 31 blog, and the parents’ results were presented in my blog from September 30. In sum, both parents and teachers agreed that play is an essential part of any child’s school day and should be fostered alongside traditional educational concepts.

I wanted, however, to see if the parents’ desires and the teachers’ stated beliefs are actually being played out — no pun intended! — in the classroom. I thought that one way to do this would be to ask those who are going through it each day — the kids themselves. I therefore asked parents of preschoolers through third-graders to speak with their children about their experiences with play at school.

Parents were asked to present their children with six multiple-choice questions and to record their answers. Questions addressed whether or not children believe they have enough time to play at school each day, what types of play they are engaging in at school, what types of play they prefer, and the reasons why they like to play at school.

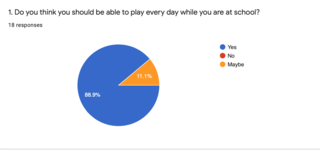

Answers from 18 children (10 males and eight females; two preschoolers, one kindergartner, two first-graders, seven second-graders, and six third-graders) were recorded. When asked if they thought they should be able to play every day while at school, 16 children (88.9 percent) said “Yes” and two children (11.1 percent) said “Maybe.” Unsurprisingly, zero children said “No.” In response to the question of whether they are given enough time to play at school, eight children (44.4 percent) said “Yes,” and 10 children (55.6 percent) said they would rather have more time. There were no differences in these responses among children of different grade levels.

Children were also asked to check off all the different times during the day at school when they were given time to play. The children selected recess/playtime (100 percent), gym class (77.8 percent), center time (16.7 percent), while doing projects/experiments (16.7 percent), while learning (22.2 percent), during brain breaks (44.4 percent), or other. Two children (11.1 percent) chose “other” and wrote in “mask breaks.” These selections did not differ by grade level.

Regarding the types of play that children prefer, they were asked whether they would choose games with rules (such as “Simon Says,” “Hot Potato,” or sports), games without rules (such as building with blocks or Lego, playing with clay or Play-Doh, drawing pictures, or playing dress-up), or whether they liked both equally. Games with rules were preferred by 16.7 percent of children, 16.7 percent said they would choose games without rules, and 66.7 percent said they liked both equally.

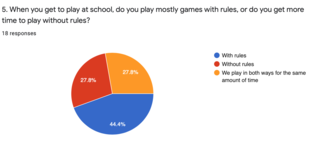

When asked whether, at school, they mostly play games with rules, without rules, or both for the same amount of time, 44.4 percent said they mostly play games with rules, 27.8 percent said they mostly play games without rules, and 27.8 percent said they play in both ways for the same amount of time. Notably, seven of the eight children who answered “with rules” were in second or third grade. This is in line with research that suggests that children develop a stronger preference for games with rules once they enter formal school.

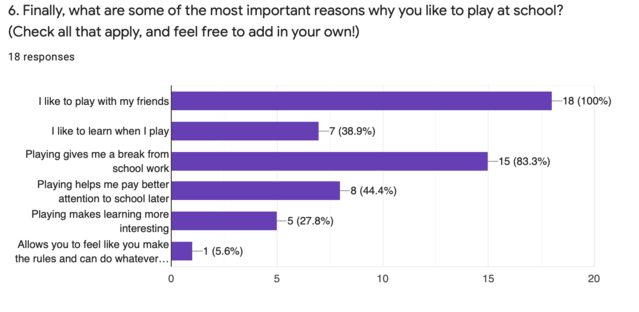

Finally, children were asked to identify some of the most important reasons why they like to play at school. They could select more than one option, or could write in their own. “I like to play with my friends” was chosen by 100 percent of children, and 83.3 percent said that playing gives them a break from school work (only the preschoolers didn’t choose this option). “I like to learn when I play” was selected by 38.9 percent of children (and one said he preferred to just “play and play”!). A good number of children (44.4 percent — all first- through third-graders) recognized that they pay better attention to schoolwork after they play. This is in line with the 92.9 percent of teachers and the 81.4 percent of parents who agreed that play helps to improve students’ attention in my previous surveys. “Playing makes learning more interesting” was chosen by 27.8 percent of children. One child wrote in a unique response, saying that playing “allows you to feel like you can make the rules and can do whatever you want.”

Overall, the results of this brief survey of a small sample of children suggest that children believe play to be an important part of their daily life. It is not surprising that most children believe they should be able to play every day while they are at school and that the majority wish they had more time to play at school.

What was particularly interesting was children’s insight into some of the ways in which playing at school can actually help them. For example, they recognized that they need the occasional break from schoolwork and that playing enables them to pay better attention later. Several also recognized that learning and play do not need to be mutually exclusive and that play can make learning more interesting.

In a world filled with uncertainty, social distancing, political tensions, and a very frightening pandemic, children need to be provided with safety, security, consistency, and — perhaps most importantly — time every day to just have fun.