Perfectionism

Understanding and Healing Perfectionism

An emotions-based perspective on a common problem.

Posted February 23, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Perfectionism can function as a protective defense.

- Understanding emotions helps loosen the grip of perfectionism.

- The Change Triangle is a guide to healing perfectionism.

As children, we have big and powerful emotions that are too overwhelming to deal with alone. Young brains and bodies need adults to calm and soothe them. But when adults won’t, don’t, or can’t soothe their children, young minds must resort to coping alone by creating defenses that prevent them from becoming emotionally overwhelmed. Perfectionism is one such defense.

Obsessing about being perfect is the action that takes us away from our emotions and a connection to our body to spare us discomfort and pain. We escape into our obsessive mind.

When people tell me they want to be perfect, I explain the Change Triangle so they can recognize and understand their perfectionistic voice and compulsions. I teach them to listen to and learn about the perfectionistic parts of their mind.

For example, I might suggest, “Can you ask your perfectionistic part how it protects you?”

If you suffer from perfectionism, maybe you could ask that part of you the same question. You might be surprised that it will answer. When we talk with our perfectionistic part(s), hokey as it may sound, we may discover the specific purpose it serves and the story of how it came to be.

For example, in a recent therapy session, my patient, who I’ll refer to as Charles, drove himself to be perfect and tortured himself for making any mistakes whatsoever. When he turned inward to ask his perfectionistic part how it was protecting him, it answered, “I protect you from making mistakes and being humiliated.”

The next part of the work entailed getting curious about the root of that belief so we could learn what it needed.

“When was the first time you remember being humiliated for making a mistake?”

I invited Charles to gently and curiously tune into that bad feeling of humiliation in his body and bridge back in time to the first memory when he had that same experience. Once we accessed an early memory, we could process the core anger towards his father for shaming him for the innocent mistakes that all children and grownups make. Charles said he needed his parents to tell him, “It’s OK. It’s no big deal. You’re still a good boy.”

After he processed his anger, other emotions like sadness and fear also needed attention and to be released from his body as well. All these emotions had been buried starting in early childhood. Without help from a grownup, these emotions could not be metabolized in a healthy way.

Now, as an adult, Charles was able to identify and experience his emotions. With practice, tools, and techniques, he could ride the full wave of his anger, sadness, and fear, allowing the emotional energy to be released. This process ushered in new and deeper states of physical and mental calmness. Charles came to truly believe that when he made mistakes, he wasn’t bad or worthy of humiliation. As a result, the defense of perfectionism was no longer needed in the same way, and its power melted away.

These principles work for us all. Once the core and inhibitory emotions are named, validated, and tended to, the brain rewires, and the symptom of perfectionism eases.

Self-help practice

*Remember to strive to be compassionate to yourself and curious when you do these exercises.

These are some of the questions I might ask in a therapy session to build greater awareness and self-connection. You can ask yourself these questions, too. Then try to answer them:

- Think of an example of where you demand perfection or cannot tolerate flaws or mess. Now, imagine a scenario where you don’t meet your standard. Who do you imagine criticizing you (besides you)?

- Was there anyone in your childhood that drove you or for whom you had to be perfect? Or who was too imperfect for you?

- How old were you when you first remember obsessing about being perfect? Can you see that child self in your mind’s eye? What exactly do you see?

- What events or relationships might have tilted your innate strivings for excellence into an unhealthy balance?

These kinds of questions are useful because awareness is the precursor to change. In other words, we cannot change what we don’t know exists. For example, if you become aware that your parents drove you too hard, you know you have to deal with the core emotions you have towards them for their lack of attunement and care.

The Change Triangle and Perfectionism

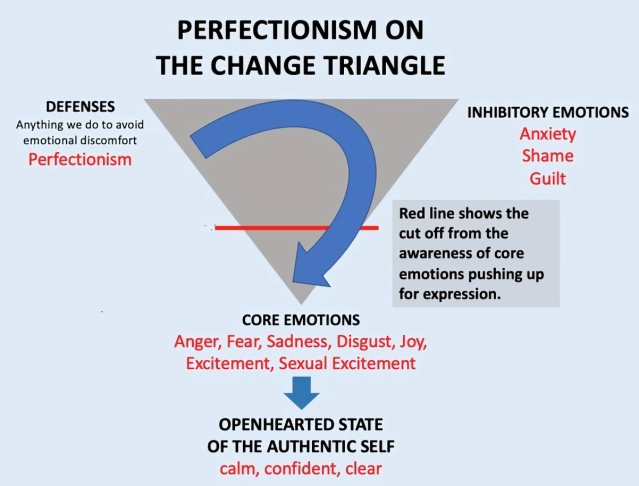

Let’s look at the Change Triangle for guidance on how to understand, loosen up the grip of perfectionism, and set the stage for healing.

The Change Triangle maps out the relationship between our perfectionism, our anxiety, shame, and guilt, our core emotions, and our authentic selves.

The above diagram shows perfectionism as a defense on the Change Triangle. A defense, by definition, is anything we do to avoid experiencing uncomfortable emotions. The purpose of all defenses is honorable. They try to protect us.

Transforming perfectionism involves:

- Recognizing it as a defense against feeling our emotions

- Practicing techniques like grounding and breathing to calm anxiety

- Transforming shame

- Naming, validating, and moving through the underlying core emotions by re-learning how to experience them fully

- Learning to relate to others from our authentic self. This requires having the courage and trust to own our shortcomings, talents, and virtues while being aware of our emotions in real time.

Working the Change Triangle each time we notice our perfectionism by getting curious about our underlying emotions slowly turns down the volume of perfectionism’s loudness and intensity. We might continue to notice perfectionistic parts of ourselves for a long time, but perfectionism will no longer rule us. It doesn’t need to because we can now tolerate our underlying emotions and deal directly with them. Best of all, we derive the benefits of spending more and more time in our authentic self. We learn to truly accept and even come to love our perfectly imperfect self.

References

Fosha, D. (2000). The Transforming Power of Affect: A Model for Accelerated Change. New York: Basic Books