Psychiatry

Asylum History From the Bottom Up

How can we capture the views of asylum patients in the history of psychiatry?

Updated May 19, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- The records left by asylums can be incredibly vast.

- It can be difficult to locate the perspective of patients in asylum records.

- By being innovative, however it is possible to paint a picture of what it was like to be in an insane asylum.

- Capturing the perspective of patients is crucial if we want to understand what asylums were really like.

Researching the history of the asylum can be a case of feast and famine, often at the same time. Some asylums left, if not mountains of records, then at least large hills. I mean that literally. An archive of a London asylum I recently visited boasted nearly 400 metres of documents. If you stacked these papers up, they would tower over the highest point in seven states.

Depending on what you’re exploring, such records can provide an abundance of riches. If you want to learn about how asylums spent and earned money, asylum accounts can tell you everything from how much it cost to heat their buildings to how much they spent on hops (many 19th-century asylums ran their own breweries). Annual reports contain the often surprising views of the medical superintendent, and sometimes the head nurse (or matron), the chaplain, or others in charge.

Locating the perspectives of patients, however, is more difficult. It’s not that there aren’t records of patients. Case notes make up a huge proportion of asylum records, as do records relating to admission, discharge, and deaths. But these voluminous case notes are written mainly by doctors. We can read what they thought of patients and their psychological state, but the patient’s own perspective doesn’t come through.

As a result, trying to chart the experiences of patients in asylums can be a little like trying to find a needle in a haystack. That doesn’t mean it isn’t possible, however.

Often, patients write memoirs based on their experiences. Some of these include the memoirs of Clifford Beers, Ebenezer Haskell, and Elizabeth Packard from the 19th century, and Susanna Kaysen (Girl, Interrupted) and Barbara Taylor (The Last Asylum) in the 20th. Only a small proportion of the hundreds of thousands of people who spent time in asylums, however, wrote down their views.

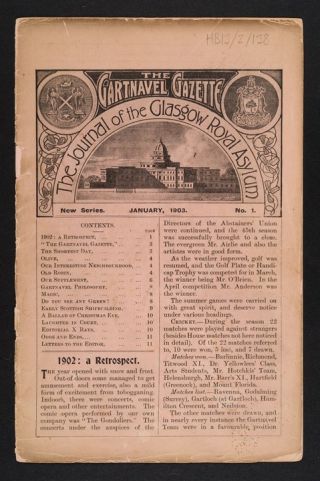

Some asylums also published periodicals, which provide an insight into patient experience. These include The Opal, from Utica State Lunatic Asylum, and the Gartnavel Gazette and New Moon, both from Scotland. These magazines include poetry, short stories, accounts of outings and activities, and even editorials about what was going on in the asylum. But we do have to consider whether such periodicals were censored by asylum authorities. Even if they weren’t, they tended to represent the views of more privileged, highly educated patients, not the majority.

Asylum photography can also provide some insights. Many admissions records include a photo of the patient, and some asylums took "before and after" shots of patients, illustrating the effectiveness of treatment. It’s clear, however, that most of these photographs were staged to varying degrees. In a series of before and after photos at San Servolo Asylum near Venice, for example (see my previous blog for more about how most patients ended up there), the ‘after’ images appear to merely show the patients in nicer clothing. Photos of the rooms and grounds in which patients spent most of their time might provide a better indication of what their days were like. While some of these, such as at Inverness District Asylum, depict quite nice interiors and relatively spacious living quarters, others show just how crowded asylums could be and how desperate the living conditions could get.

A more painstaking way of capturing at least a semblance of a patient’s perspective can be to piece together a variety of asylum records. Admissions records typically provide basic details about a patient, including their occupation, age, religion, suspected cause of mental illness, and the events that led them to the asylum. These can then be cross-referenced with other documents and information about the asylum.

Case notes, while from the physician’s perspective, can provide a sketch of a patient's daily activities, including whether they worked somewhere in the asylum or spent most of their time in bed. They, along with clinical records, can also detail whether the patient had to cope with illness or injuries.

Ward books or day books, written by nurses, chart the daily routine of patients. They often list patients by name, particularly those who cause trouble (by fighting, destructive behavior, or refusing food), those struggling with illness, and those receiving special treatments, such as hydrotherapy (therapeutic baths or showers).

Patients also get discussed occasionally in letters written by superintendents and also in annual reports. While these patients are often ‘success stories,’ sometimes they are mentioned to make a point. For instance, an annual report from the 1840s, detailing the case of an Irish migrant who ended up at a London asylum, argued that desperate poverty was behind this patient’s illness. It added that early identification and support of such unfortunate people might lead to fewer people ending up in asylums and/or quicker recoveries.

Although this patient isn’t identified by name, it would be possible to go through the admissions records and identify him and then use other documents to chart his progress (he was a success story). Even financial records about what was spent on clothing, food, and fuel can give a sense of whether patients were well-clothed, well-fed, and warm. As we saw from the hops receipts, patients at some asylums drank beer, too. Collating all of these disparate records can be a painstaking and slow process, given the way asylum documents were recorded, but it can begin to paint a picture of a patient’s experience.

Recovering the views of patients in asylums is a challenging task, but it is a necessary one if we want to piece together a more accurate picture of what asylums were like to live in. Asylums were not all created equal. No asylum was created to be a terrible place, but some ended up being just that. Other asylums, however, did their best to make life comfortable for patients who would have been in dire straits otherwise. For some, the asylum could be a sanctuary from a hostile world, a place where a patient could engage in activities designed to give their lives meaning and, possibly, a chance at recovery. Asylum history is nuanced and complex, but tracing the experiences of patients is the best way to understand it.

References

Taylor, B. (2015). The Last Asylum. London: Penguin.

Coleborne, C. (2020) Why Talk About Madness. Basingstoke: Palgrave.