Anxiety

Understand Worry and Create a Brighter Future for Yourself

Seeing worries in terms of possible future selves can make them work for you.

Updated November 5, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Our self-concept includes many possible selves—some real, some imagined, some in the past, some yet to be.

- Worry should prompt us to create detailed accounts of futures in which the worst, and the best, happen.

- Identifying the evaluative selves that cause worry can help bring about brighter alternative future selves.

Things are seldom as we would like, including ourself. Or, ourselves—plural because each of us are many. To paraphrase Walt Whitman, we each contain multitudes. In most cases, it’s an unruly bunch.

I am referring to self-concepts and their many facets: what we think we are like, once were, will be, might be, should be, or would like to be, to name just a few. A few of “us."

Lots of Moving Parts, Not All Going in the Same Direction

Selves have many components, including traits (“I am introverted”), events (“I was born in Brooklyn”), social identities (“I am a first-generation college graduate”), and images (“I am tall and thin”). While those examples are descriptive, others are evaluative, including prescriptions (“I should develop more hobbies”) and proscriptions (“I should not dwell on the past”).

Carl Rogers worked with the “ideal self,” the way we’d like to be, and the “actual self,” what we think we’re really like. He described the emotional problems that stem from discrepancies between the two, and how psychotherapy can bring them together.

We often ruminate about actual-ideal self-discrepancies. But, having already considered the potential benefits of a greater understanding of rumination, and of associated negative emotions, let’s examine worry. Worry, like rumination, involves extended, thematically-related, repetitive sequences of covert self-talk. It is very often negative in valence, and only partially under conscious control.

Like rumination, worry often contains unfavorable judgments that reflect internal evaluative standards, such as are implied by our ideal self. The difference is that, for worry, the object of evaluation lies ahead, a possible future event or circumstance, rather than in the past as in rumination.

Worry is therefore about future selves. We worry about hypothetical future scenarios that are undesirable, and therefore, non-preferred. For example, ones involving psychological or physical harm or loss. Future selves that worry us are one example of what Markus and Nurius (1986) referred to as “Possible Selves."

A possible future self is worrisome because it is discrepant with another, preferred self and this causes negative emotions. Higgins (1987) proposed that an actual-ideal self-discrepancy generates a negative affect characterized by dejection, whereas for an actual-ought self-discrepancy, the negative affect involves agitation. The latter is more likely the basis for worry.

Preferred selves imply harms to avoid, losses to mitigate, goals to achieve, standards to be met, expectations to satisfy. Fears and hopes, opportunities and obstacles. Or, you could say, the threat of harm or loss, and goals, standards, and expectations imply different selves. Because often it is the threat or goal we have explicitly in mind, rather than an elaborated picture of the possible self that it entails, which frequently is more implicit.

Fears and Hopes Imply Selves

The distinction between a narrowly-defined threat or goal (“I want a promotion”) and the corresponding self (“This is how life would be after promotion…”) is important. We stand to gain insight by imagining our future self, fully blown, in all its detail and implications. What we would be like if we were to experience or avoid the harm or loss, achieve or fall short of a goal, or otherwise satisfy or violate an evaluative standard.

We should examine our worries and recognize and familiarize ourselves with the underlying self-discrepancies. This requires a process of active self-elaboration in which we identify and flesh out the features of relevant preferred selves and decide which to take seriously, and which should be tweaked or discarded because they are unrealistic or counterproductive. Concrete benefits may follow.

You are already familiar with occasions when something like this happens. Financial planners use software to project clients’ post-retirement income and lifestyle under different assumptions about retirement age, inflation, market trends, and living expenses. Different assumptions generate different projections, which are, in effect, possible future selves.

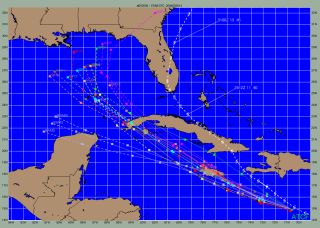

Similarly, hurricane tracking leads to projections of various different paths a storm might take, as indicated by forecasting models that make different meteorological assumptions. These have implications both for the hurricane and for the possible future selves of those who live along those paths.

Psychology offers several concepts for processes in which we envision possible future selves: mental simulation (Rivkin & Taylor, 1999), episodic future thinking, mental time travel, episodic foresight, and prospection (Du et al., 2022). Evidence suggests these can facilitate decision-making, problem-solving, and the achievement of goals.

Your Future Self Is in the Details

The vividness and level of detail in which possible future selves can be imagined may be important. We can precisely locate specific events we foresee our future self encountering in time, in a particular place, and in the context of specific individuals and surroundings. We can envision our actions and those of others, and our subjective experiences, including what we would think, feel, hear, see, smell, taste, and touch.

Anxiety appears associated with high levels of detail and vividness in thinking about possible negative scenarios, but lower detail and vividness for positive ones. This may be advantageous in preparing us for undesired outcomes. But it also may represent an unrealistically negative sense of our future self.

Road Trip

This suggests an exercise you may wish to try. Just like journaling about the day’s events, we can spend time each day writing about a possible future self. This could involve projections about what things would be like if we do, or do not, achieve a certain goal, such as earning a promotion at work. Or about an anticipated transition that we believe would bring a mix of good and bad outcomes, such as a new job, moving, or beginning or ending a relationship.

This takes to a new level the common suggestion to list likely positive and negative consequences of important decisions before making them. We can create a narrative featuring the future self to which each choice would lead. They can be populated with specific episodes that we imagine, with details that bring it to life in our minds. The diverging timelines could be extended far into the distant future, in all their implications and ramifications.

If this sounds like too big a project, consider that it can be done just a few times a week in fairly brief sessions (King, 2001). And it can be done in outline form at first, listing specific episodes, settings, and outcomes.

To paraphrase Yogi Berra, if you come to a fork in the road, go both ways; then decide which path to take.

Copyright 2023 Richard J. Contrada.

References

Bailey, J. ‘’If You Come to a Fork in the Road, Take It’’: Yogi-ism’s for Tough Times.

Du, J. Y., Hallford, D. J., & Busby Grant, J. (2022). Characteristics of episodic future thinking in anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 95, 102162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102162

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

King, L. A. (2001). The Health Benefits of Writing about Life Goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(7), 798–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201277003

Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41(9), 954–969. APA PsycInfo <1967 to 1986>. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954

Rogers, C. R. (1989). The carl rogers reader. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Rivkin, I. D., & Taylor, S. E. (1999). The Effects of Mental Simulation on Coping with Controllable Stressful Events. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(12), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672992510002

Schmidgall, G. (2014). Containing Multitudes: Walt Whitman and the British Literary Tradition. Oxford University Press.