Anxiety

Do You Have “Coronaphobia”?

Adaptive vs. Maladaptive Anxiety.

Posted December 29, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Remember Goldilocks and the Three Bears? First the porridge was “too hot,” then it was “too cold,” and then it was “just right.” That is how it feels with anxiety right now.

“Too hot.”

Some days, if I am a little under the weather, or if I stay up too late watching all the bad news, my anxiety skyrockets, and my sleep is disrupted. Most of us have had COVID nightmares at least a few times this year.

“Too cold.”

Other days, I may head out for a walk and forget my mask. Last week, I excitedly said “yes” to a hosting an out of town guest without even thinking through the possible consequences.

“Ah, just right.”

Then sometimes in the evening or on the weekend I relax at home and let fears of COVID-19 fade from my mind completely as I lose myself in a good book or show.

Many people have asked me how my patients are doing during the pandemic, and I say “about the same as all of us.” Reactions among friends, family, and patients range from those who have greatly benefited by the social changes brought about by quarantine to those who are too terrified or depressed to leave their home. Most fall somewhere in the middle and vacillate depending on the hour, day, or week. It is so hard to get it “just right.”

Uncertainty is one of the hardest experiences for humans to manage. Yet fear of the unknown is a normal and adaptive mechanism evolved over millions of years to help us keep ourselves safe. We literally could not live without it. Unfortunately, the very same brain mechanisms that help us navigate the unknown can spin out of control and cause wild swings of either too much anxiety or too little.

How do we know when fear is adaptive or when it is becoming the problem?

Typically, we define the impact of mental health symptoms by how much impairment they cause in our daily functioning. This is very tricky, as most of our lives are quite disrupted. Staying home and avoiding social gatherings and crowds are no longer an indication of a psychological issue. Instead, these actions are actually the desired result of following the advice of health experts.

Mental health professionals trying to distinguish between adaptive anxiety and subsequent behavior change have described a new disease they are calling “Coronaphobia.” The term was first coined in March of 2020 by two Canadian psychologists, Drs. Asmundson and Taylor, when very few cases were reported in the US, yet fear was rapidly escalating. Obsessive behaviors, distress, avoidance reaction, panic, anxiety, hoarding, paranoia, and depression are some of the responses associated with Coronaphobia.

Research on the psychological reactions to previous epidemics and pandemics, along with concepts such as psychology’s Big Five traits (Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism) suggests that various psychological vulnerability factors may play a role in who develops maladaptive anxiety. Individual differences such as the intolerance of uncertainty, perceived vulnerability to disease, and anxiety proneness all make one more susceptible to developing Coronaphobia. On the other spectrum, there are those who are “too cold,” as in not having an appropriate level of respect for the threat, and may engage in many high risk behaviors or have a cavalier attitude about the likelihood of infection.

Within the context of the Big 5 personality traits, there is a wide range of people who can fall across the full spectrum of responses to COVID 19. For example, those with high Neuroticism may be particularly prone to “too hot” anxiety, while those with low Neuroticism may be more prone to “too cold”. Combinations of Big 5 traits can also pull us in various extreme directions, such as low Neuroticism plus high Openness to Experience, which can lead to the “too cold” and cavalier mindset. High neuroticism plus low openness to experiences can create the propensity for the “too hot” mindset.

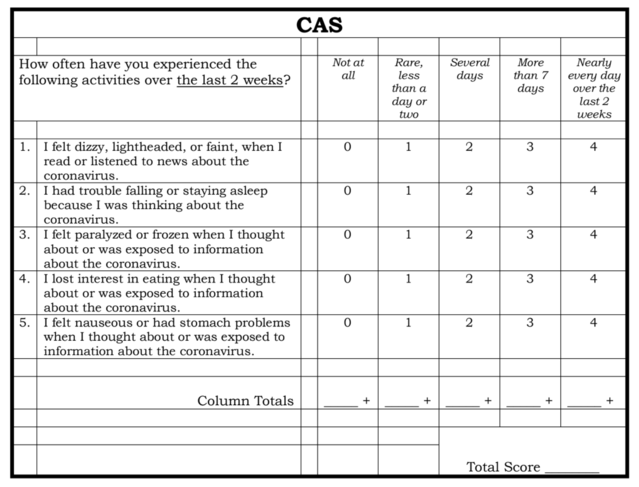

Investigators have reported that five symptoms — dizziness, sleep disturbances, tonic immobility, appetite loss, and nausea/abdominal distress — are strong predictors distinguishing Coronaphobia from otherwise normal concerns about COVID-19 that do not result in functional impairment. They are working on validating a self-reported mental health screener for this condition. You can take the quiz yourself and see where you fall. Scores of nine or above indicate you may be suffering from Coronaphobia.

For now, as I say not just to my patients, but to my friends and family, err on the side of caution. Stay safe and mostly at home. Venture out when necessary with all the proper precautions. Humans are social creatures, and we need one another. This is indeed a challenging time. Try to remember that this too shall pass, and we will eventually return to a more varied and fulfilling lifestyle. Remember we are all part of “humanKIND” so protect yourself and others. We continue to be in this together.